Other IPRI Publications

Conflict Weekly

April 2024 | IPRI # 437

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Conflict Escalation in the Middle East, and One Year of Civil War in Sudan

read more

Conflict Weekly

April 2024 | IPRI # 436

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Six Months of War in Gaza & the Mexico-Ecuador spat

read more

Conflict Weekly

April 2024 | IPRI # 435

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Remembering the Rwandan Genocide and Martin Luther King

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2024 | IPRI # 434

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

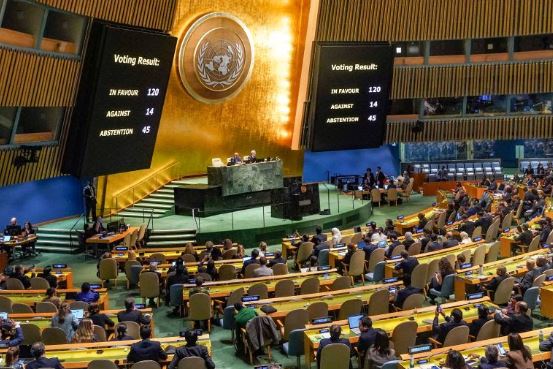

UNSC Resolution on Gaza, Terror Attack in Moscow, and a Profile of the IS-K

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2024 | IPRI # 433

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Female Genital Mutilation bill in The Gambia, Search for a Ceasefire in Gaza and Continuing Instability in Haiti

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2024 | IPRI # 432

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Continuing Kidnappings in Nigeria

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2024 | IPRI # 431

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Enshrining Abortion Rights in France's Constitution, Inuit Women's Demand for Justice, the State of Emergency in Haiti and the Elusive Ceasefire in Gaza

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2024 | IPRI # 430

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Sweden in NATO, Farmers' Protest in Poland, and the anti-LGBTQ bill in Ghana

read more

Conflict Weekly

February 2024 | IPRI # 429

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

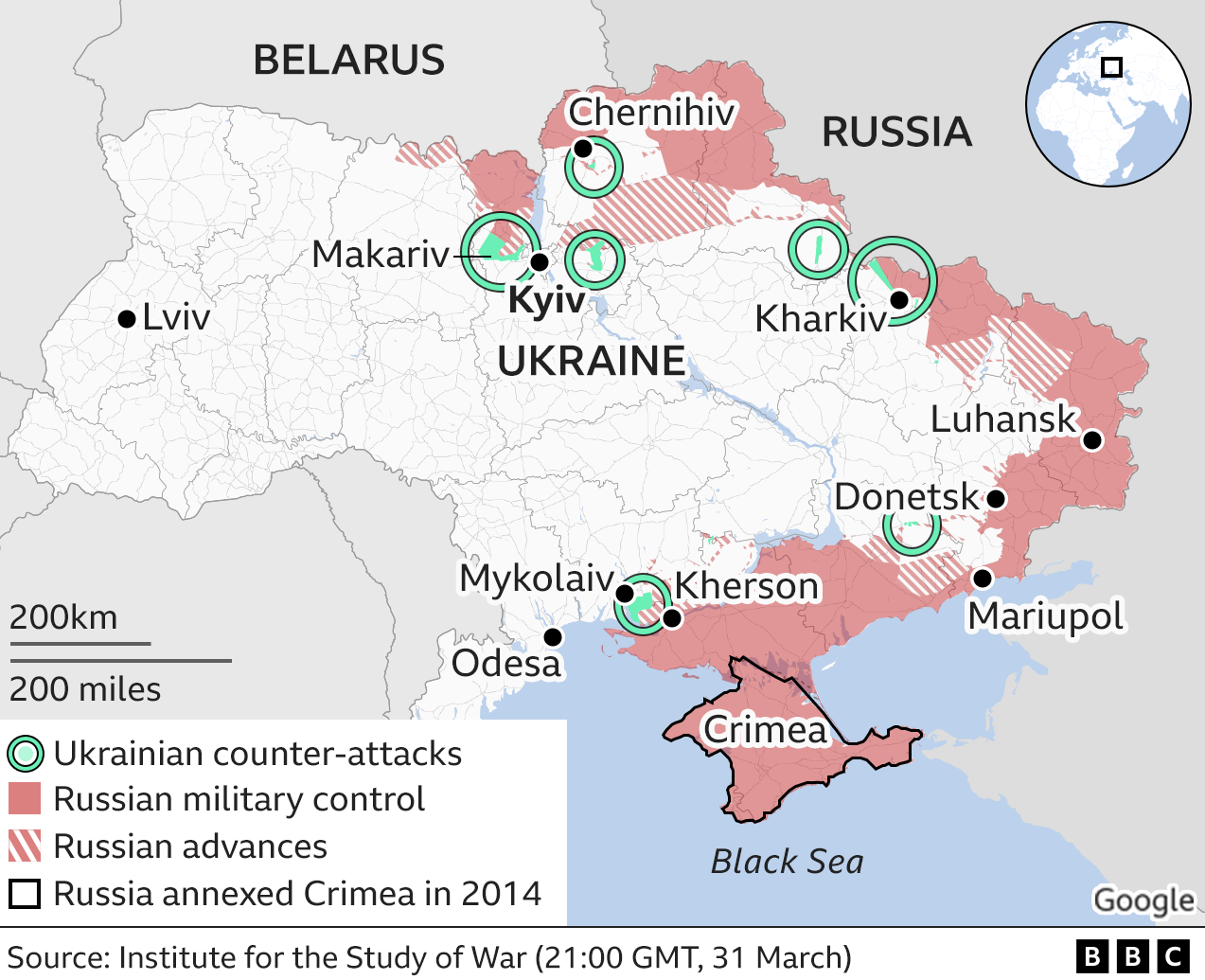

The Battle for Avdiivka in Ukraine

read more

Conflict Weekly

February 2024 | IPRI # 428

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

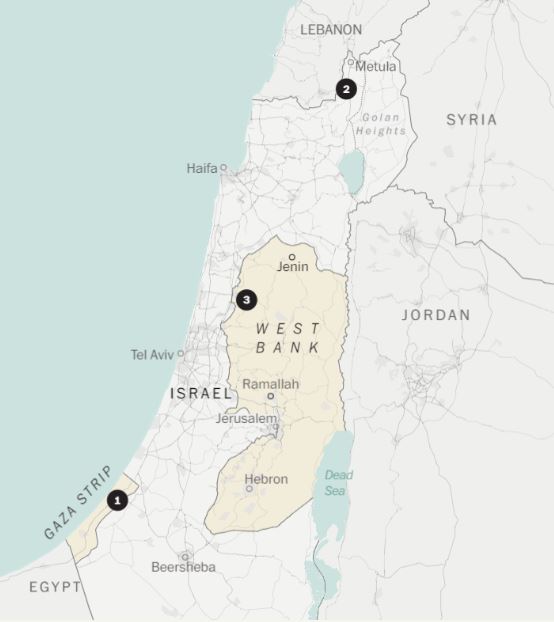

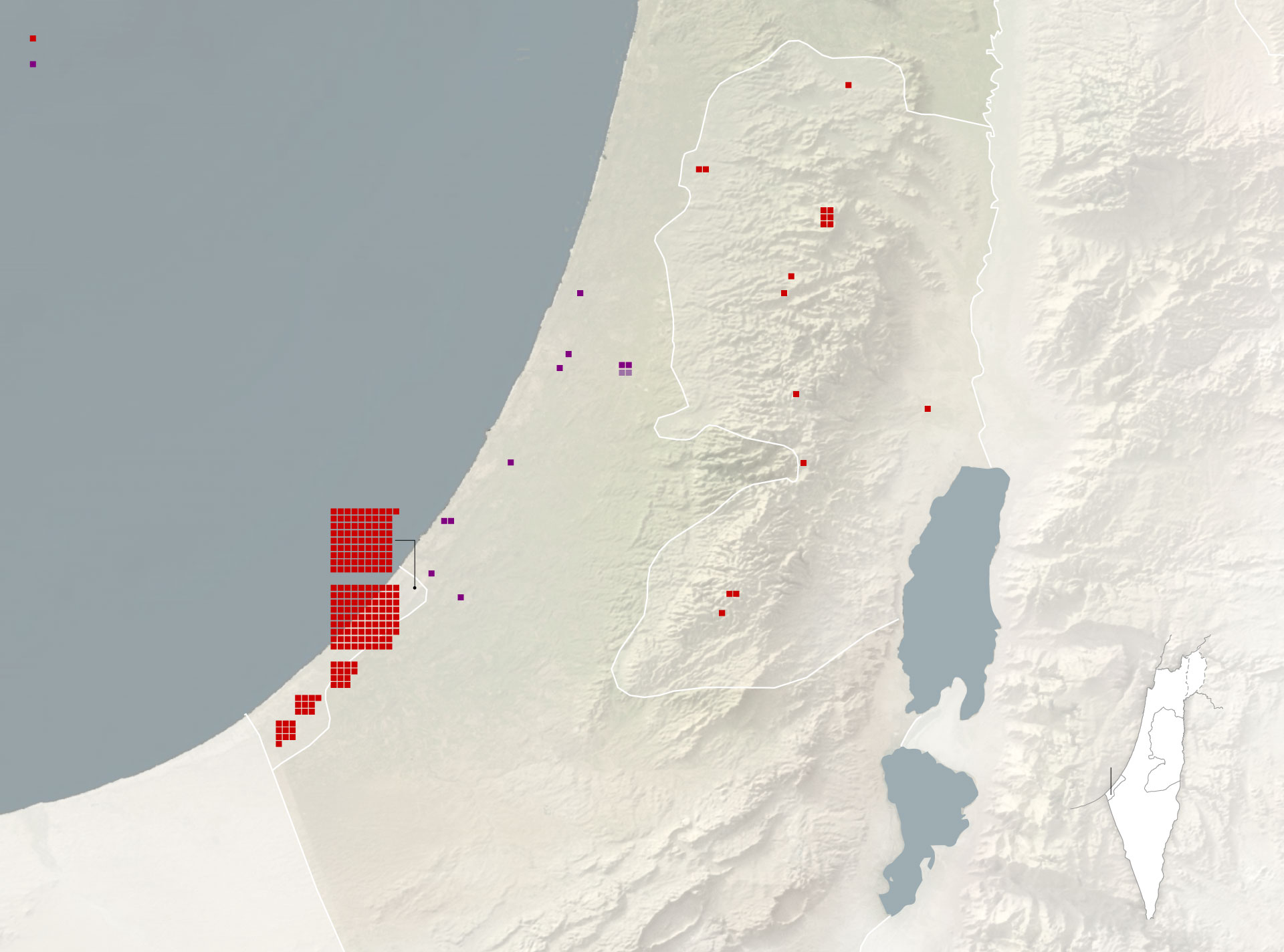

Israel's Military Campaign in Rafah

read more

Conflict Weekly

February 2024 | IPRI # 427

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Protests in Senegal

read more

Conflict Weekly

February 2024 | IPRI # 426

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

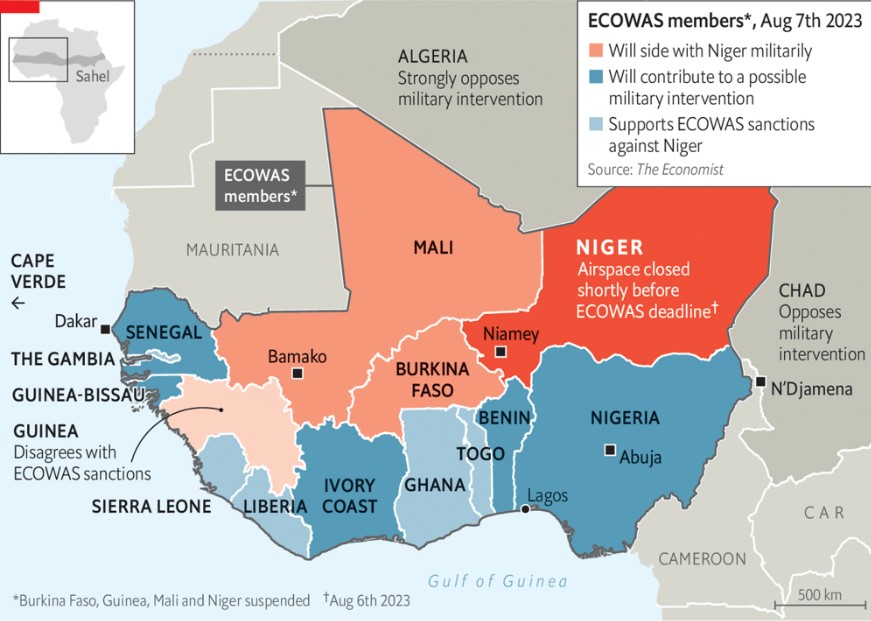

UNRWA 's funding crisis in Gaza, Farmers' protest in France, and Withdrawal of Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger from ECOWAS

read more

Conflict Weekly

January 2024 | IPRI # 425

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Continuing Violence in Haiti, Myanmar and Gaza

read more

SPECIAL COMMENTARY

January 2024 | IPRI # 424

IPRI Briefs

Bibhu Prasad Routray

Myanmar: Ethnic Armed Organizations, China’s Mediation and Continuing Fighting

read more

Conflict Weekly

January 2024 | IPRI # 423

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Red Sea Crisis: Attacks and Counter Attacks

read more

Conflict Weekly

January 2024 | IPRI # 422

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

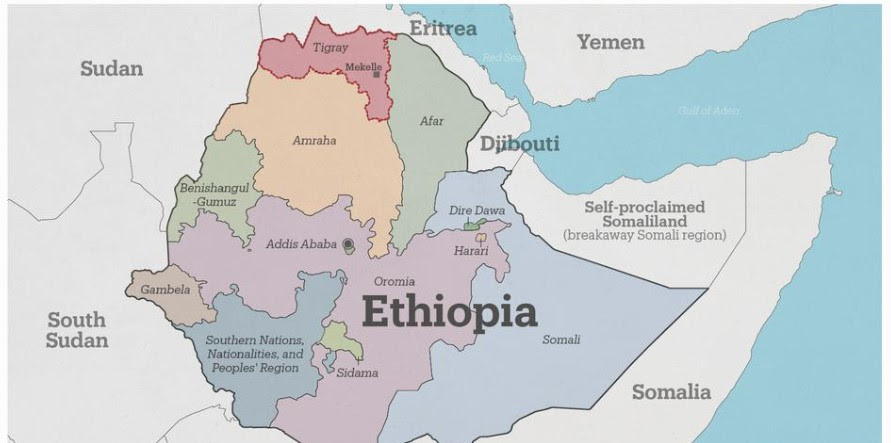

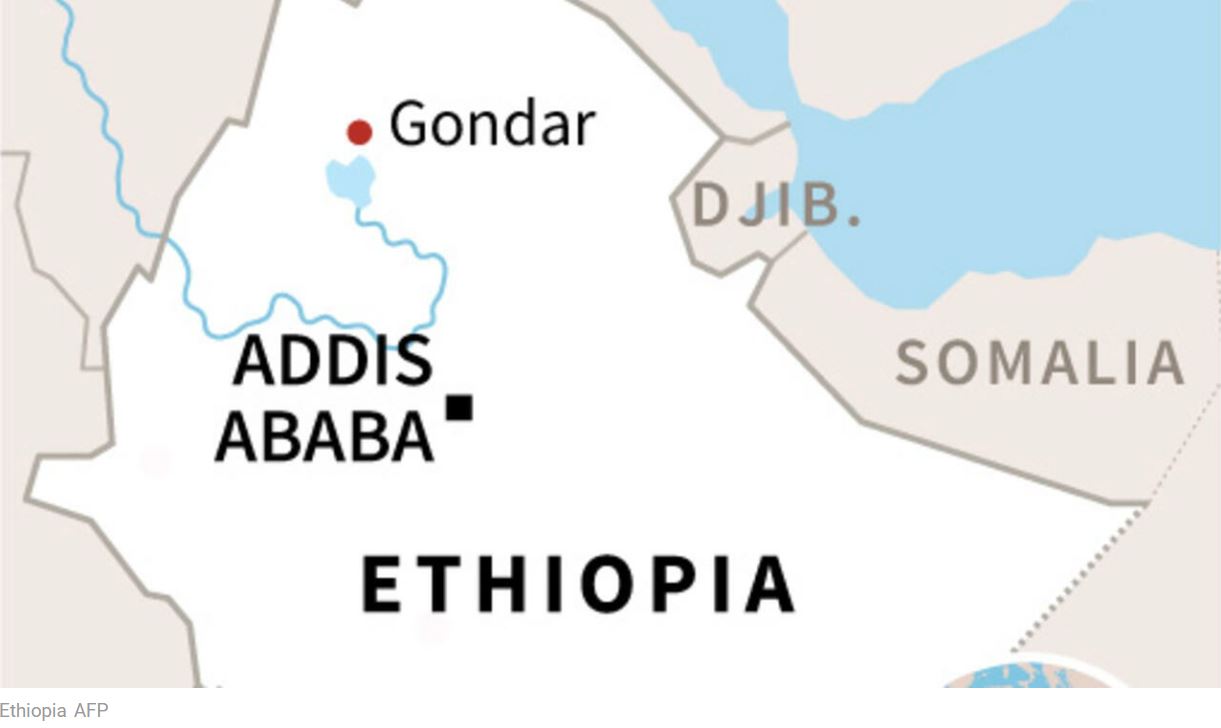

Blinken's Fourth Visit to Middle East, Ecuador's State of Internal Armed Conflict, and Ethiopia-Somaliland tensions in the Horn of Africa

read more

Conflict Weekly

January 2024 | IPRI # 421

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The War in Ukraine and Gaza

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2023 | IPRI # 420

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Special Edition: Conflicts in 2023

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2023 | IPRI # 419

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Red Sea Crisis and Hungary's blockade of EU's Ukraine aid

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2023 | IPRI # 418

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Tensions in South China Sea and Ukraine and Terror Attack in Pakistan

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2023 | IPRI # 417

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

End of a Fragile Peace in Gaza, and a Failed Coup in Sierra Leone

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2023 | IPRI # 416

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Floods in East Africa, the London Summit on Global Food Security, and the War in Gaza

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2023 | IPRI # 415

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Into the Fifth Week: The Continuing Ground Offensive and Israel’s Search for Hamas’ Command Centre

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2023 | IPRI # 414

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Conflict in Sudan and Pakistan's Repatriation of Illegal Refugees

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2023 | IPRI # 394

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Worsening Situation in Gaza, Rapprochement between Venezuela and the US, and the Philippines- China Maritime Dispute

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2023 | IPRI # 393

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Conflict Escalation in Israel and the Failed Indigenous Voice Referendum in Australia

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2023 | IPRI # 392

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Israel-Palestine Conflict and Earthquake in Afghanistan

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2023 | IPRI # 391

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Rising security threats after the coup in Niger

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2023 | IPRI # 390

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Nagorno-Karabakh and the End of the Republic of Artsakh

read more

Conflcit Weekly

September 2023 | IPRI # 389

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Violence and Ceasefire in Nagorno-Karabakh, Auto Workers’ Strike in the US, Fighting in Sudan, Another Migrant Crisis in Italy, and the US-Iran Prisoners Exchange

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2023 | IPRI # 388

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Decriminalisation of Abortion in Mexico, Continuing Violence in Sudan, Floods in Libya, and Earthquake in Morocco

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2023 | IPRI # 387

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Fall of Black Sea Grain Initiative, Leadership Troubles for Myanmar in ASEAN, and Post-Coup Tensions in Gabon

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2023 | IPRI # 386

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Coup in Gabon and One Year of “Total Peace†in Colombia

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2023 | IPRI # 385

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Another Conflict in Ethiopia and a Stalemate in Niger

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2023 | IPRI # 384

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Political Violence in Ecuador, Wildfires in Hawaii, and Two Years of Taliban Rule

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2023 | IPRI # 383

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Continuing Standoff in Niger, Expanding War in Ukraine, and Political Crisis in Senegal

read more

IPRI Quarterly Forecasts

August 2023 | IPRI # 382

IPRI Briefs

S Shaji

Increasing Insurgency in East Africa: Major Trends and Trajectories

read more

Conflict Weekly

July 2023 | IPRI # 381

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Coup in Niger, Violent anti-government demonstrations in Kenya, and Protests in Israel over judicial reforms

read more

IPRI Quarterly Forecasts

July 2023 | IPRI # 380

IPRI Briefs

Bibhu Prasad Routray

Myanmar Continues to Burn

read more

IPRI Quarterly Forecasts

July 2023 | IPRI # 379

IPRI Briefs

Bibhu Prasad Routray

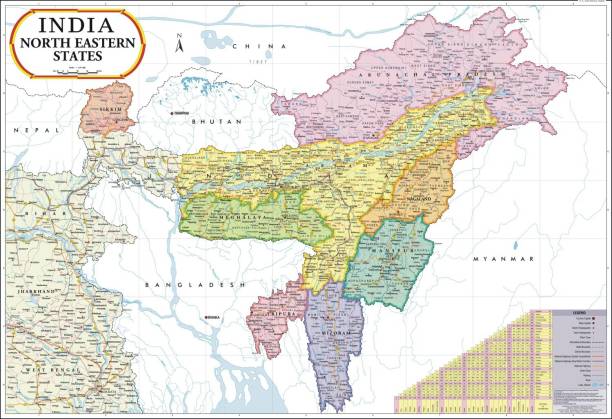

Return of Violence in Manipur

read more

Conflcit Weekly

July 2023 | IPRI # 378

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Fukushima waste water controversy, Russia’s withdrawal from the grain deal, Stalemate of aid extension in Syria, and Extreme weather anomalies across US Europe and Asia

read more

Conflcit Weekly

July 2023 | IPRI # 376

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Protests in France, Termination of UN Mission in Mali, and Violence in Israel

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2023 | IPRI # 375

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Rise and Fall of the Wagner Revolt, Failure of the Ninth Ceasefire in Sudan, and the Global Gender Gap Report

read more

IPRI REVIEW

June 2023 | IPRI # 374

IPRI Comments

Rishika Yadav, Sneha Surendran, Sandra D Costa, Ryan Marcus, Prerana P and Nithyashree RB

Global Gender Gap Report 2023: Regional Takeaways

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2023 | IPRI # 373

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Violence in Uganda, Migrant Crisis in the Mediterranean, State of the Climate in Europe, and Taliban Arms Management

read more

SPECIAL COMMENTARY

June 2023 | IPRI # 372

IPRI Comments

Bibhu Prasad Routray

The Civil War in Myanmar: Continuing Violence, the Battle of Attrition, and the Divide within ASEAN

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2023 | IPRI # 371

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Counter-Offensive and Drone Attacks in Ukraine, and Continuing Violence in Manipur

read more

SPECIAL COMMENTARY

June 2023 | IPRI # 370

IPRI Comments

Bibhu Prasad Routray

India: Violence continues in Manipur

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2023 | IPRI # 369

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Canada's Wildfires, and Reviews of two reports on Tigray and the Arctic Ice-melt

read more

IPRI REPORT REVIEW

June 2023 | IPRI # 368

IPRI Comments

Varsha K and Nithyashree RB

Hunger Hotspots: Five Takeaways of FAO‑WFP report on food insecurity

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2023 | IPRI # 367

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Russia-Ukraine Drone Warfare, Violence in Kosovo, and a Separatists' Crisis in Cameroon

read more

Conflict Weekly

May 2023 | IPRI # 366

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Bhutan's Gross National Happiness, Return of Syria to the Arab League, Seventh Ceasefire in Sudan, Bakhmut Battle in Ukraine, Zelensky's Diplomatic Offensive, and WMO Report Takeaways

read more

Conflict Weekly

May 2023 | IPRI # 365

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Armenia-Azerbaijan Stalemate

read more

May 2023 | IPRI # 364

IPRI Briefs

Bibhu Prasad Routray

Violence in India's Manipur: Clash of Perceptions of Marginalization and Victimhood

read more

Conflict Weekly

May 2023 | IPRI # 363

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Another ceasefire in Sudan, and a Counteroffensive in Ukraine

read more

Special Commentary

May 2023 | IPRI # 362

IPRI Comments

Akriti Sharma

Droughts in East Africa: A climate disaster

read more

Special Commentary

May 2023 | IPRI # 361

IPRI Comments

Bibhu Prasad Routray

The State of Conflict in Myanmar: Violence, Counter-Violence, and the Current Impasse

read more

Conflict Weekly

April 2023 | IPRI # 360

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Evacuation in Sudan, and the Chinese Ambassador's statement on the status of former Soviet republics

read more

Conflict Weekly

April 2023 | IPRI # 359

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Violence in Sudan and the Battle for Bakhmut

read more

Conflcit Weekly

April 2023 | IPRI # 358

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Violence in Israel and 25 years of the Good Friday Agreement

read more

Conflcit Weekly

April 2023 | IPRI # 357

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Protests in Israel, Elections in Finland, and Kidnapping in Nigeria

read more

Conflcit Weekly

March 2023 | IPRI # 356

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Sri Lanka's IMF deal and Violence in Haiti

read more

Conflcit Weekly

March 2023 | IPRI # 355

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

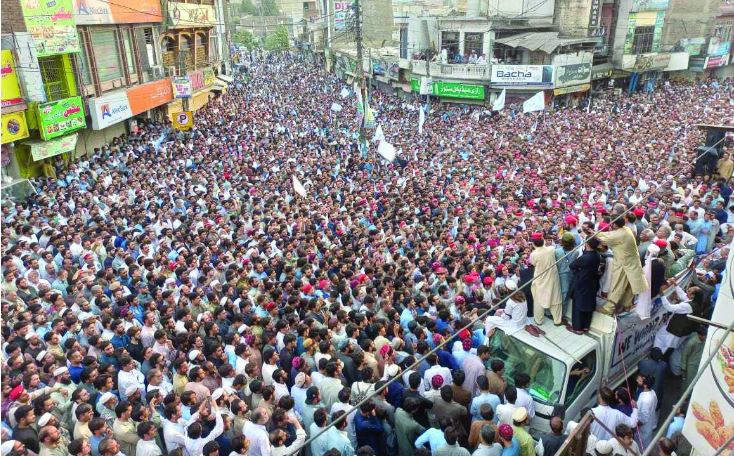

Protests in Senegal, Imran Khan's arrest attempt and Bank distress across the US and Europe

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2023 | IPRI # 354

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Protests in Georgia, Japan-South Korea reconciliation, and Iran’s school poisoning

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2023 | IPRI # 353

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

New BREXIT deal on Northern Ireland, battle for Bakhmut and return of violence in Palestine

read more

Conflict Weekly

February 2023 | IPRI # 352

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Protests in China and France, and post-earthquake crises in Turkey and Syria

read more

Special Essay

February 2023 | IPRI # 351

IPRI Comments

Bibhu Prasad Routray

Myanmar: Two years since the coup

read more

Conflict Weekly

February 2023 | IPRI # 350

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The US-China tensions over balloon, and Weather anomalies in the Americas

read more

Conflict Weekly

February 2023 | IPRI # 349

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The continuing crisis in Israel

read more

Conflict Weekly

January 2023 | IPRI # 348

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Protests in Spain, Sweden and Israel

read more

Conflict Weekly

January 2023 | IPRI # 347

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Population decline in China, and Protests in Peru

read more

NIAS Africa Studies

January 2023 | IPRI # 346

IPRI Comments

Sruthi Sadhasivam

Instability in West Africa: The role of France

read more

Conflict Weekly

January 2023 | IPRI # 345

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The new push in the Ukraine war, Ben Gvir’s visit to al Aqsa, Mali's pardon to Ivorian soldiers, violent protests in Brazil and violence over Guzman's arrest

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2022 | IPRI # 343

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Peace and conflict in 2022: Top 50 stories from around the world

read more

NIAS-IPRI Brief

December 2022 | IPRI # 342

IPRI Briefs

Devansh Agrawal

One China Policy and Absence of the Rule of Law: A brief look into the mistreatment of Tibetan refugees in Nepal

read more

Conflict Weekly Cover Story

December 2022 | IPRI # 341

IPRI Briefs

Bibhu Prasad Routray

Another Peace Accord in India’s Northeast: A review of the new agreement between New Delhi, the Assam government and Adivasi insurgent groups

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2022 | IPRI # 340

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

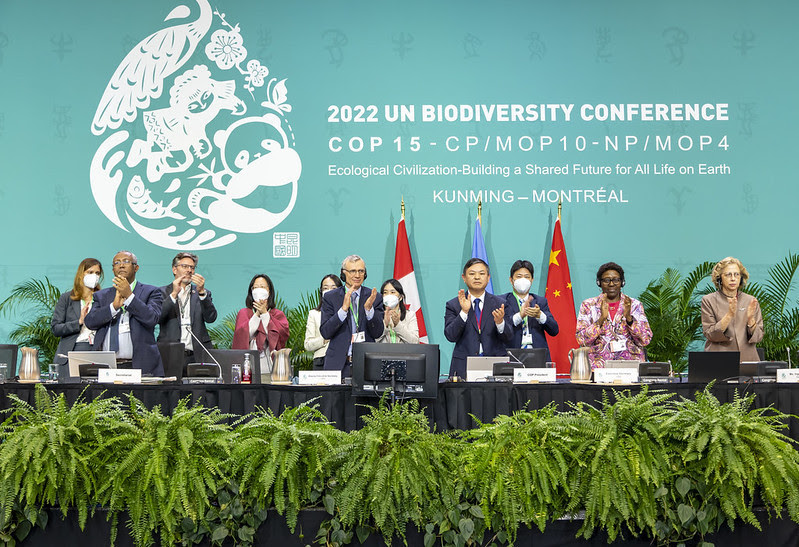

Global Biodiversity Framework and the EU's gas price capping regulation

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2022 | IPRI # 339

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Workers strike in the UK

read more

Conflict Weekly

.jpg)

December 2022 | IPRI # 338

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Drone attacks in Russia

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2022 | IPRI # 337

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Protests in China and the end of TTP's ceasefire in Pakistan

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2022 | IPRI # 336

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

A ceasefire in DRC and a report on the repatriation from Syria's detention camps

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 335

IPRI Comments

Debangana Chatterjee

Mapping Gender: Iran and its ‘Burning’ Hijabs

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 333

IPRI Comments

Sindhu Radhakrishna

Peace and Conflict in Human Wildlife Interactions

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 332

IPRI Comments

Padmashree Anandhan

Europe: Ukraine War and the Nordic

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 331

IPRI Comments

Porkkodi Ganeshpandian

Haiti: Five issues fueling gang violence

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 330

IPRI Comments

Sruthi Sadhasivam

Latin America: Four implications of War in Ukraine

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 329

IPRI Comments

S Shaji

Africa: A war and truce between Ethiopia and Tigray

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 328

IPRI Comments

Anu Maria Joseph

Africa: Ethiopia-Tigray ceasefire, and the complex roadmap for peace

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 327

IPRI Comments

Poulomi Mondal

Africa: End of Operation Barkhane, and future implications for France and Sahel

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 326

IPRI Comments

Devjyoti Saha

Africa: The Wagner Group, exploitation of conflicts and increased dependency on Russia

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 325

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

Africa: An overview and reasons behind persistence of conflicts

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 324

IPRI Comments

Athar Zafar

South Caucasia: Prospects for a stable peace

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 323

IPRI Comments

Abigail Miriam Fernandez

Afghanistan: The Taliban, women, and how history repeats itself

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 322

IPRI Comments

Vijay Anand Panigrahi

Pakistan: TTP, failed peace negotiations, and violence in Swat

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 321

IPRI Comments

Sourina Bej

India: Protracted Talks and Elusive Peace in the Naga ceasefire agreement

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 320

IPRI Comments

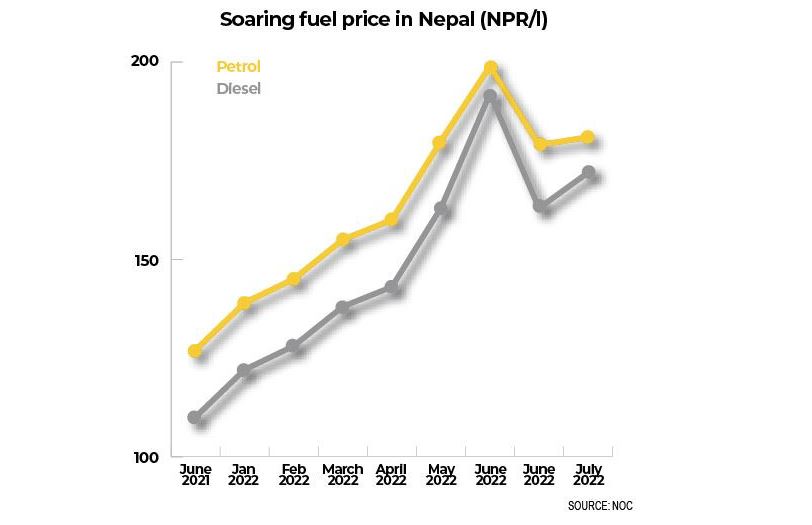

Mahesh Bhatta

Nepal: An impending economic crisis

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 319

IPRI Comments

Aparupa Bhattacherjee

Sri Lanka: Significance of Aragalaya as a unifying factor

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 318

IPRI Comments

Bibhu Prasad Routray

Myanmar: Resilience of the Opposition’s Armed Uprising

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 317

IPRI Comments

Sandip Kumar Mishra

East Asia: North Korea’s Missile Provocations

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 316

IPRI Comments

Avishka Ashok

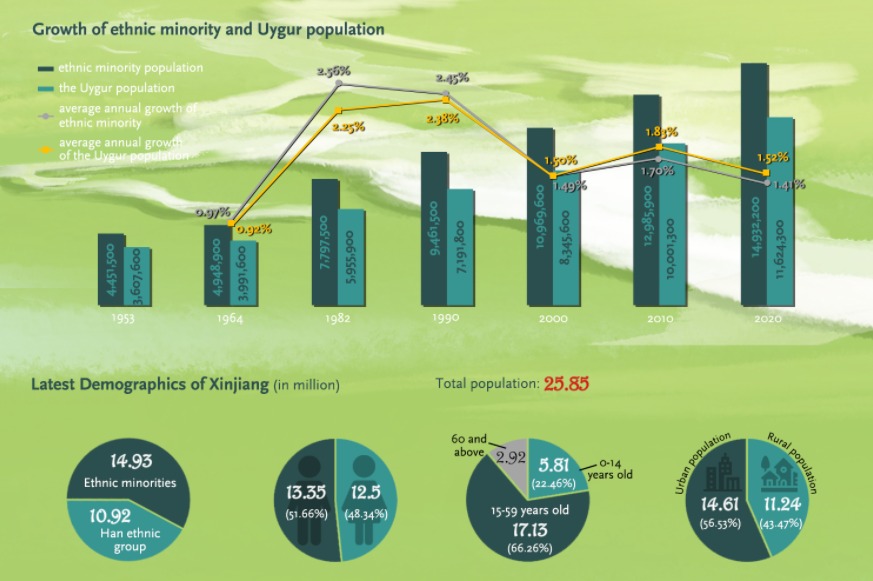

China: Global Focus and its impact on Xinjiang and the Uyghurs

read more

Conflict Weekly Special Issue

November 2022 | IPRI # 315

IPRI Comments

Mallika Joseph

The struggle to frame peace

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2022 | IPRI # 314

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Special Edition: 150th Issue of Conflict Weekly

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2022 | IPRI # 313

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Assassination attempt on Imran Khan and Russia’s withdrawal from Kherson

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2022 | IPRI # 312

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Permanent ceasefire in Ethiopia and a report on the supply chain behind war crimes in Myanmar

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2022 | IPRI # 311

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Protests and violence in Chad

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2022 | IPRI # 310

IPRI Comments

Haiti's Gang Violence, Venezuelan Migrants and the US, and Global Hunger Index

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2022 | IPRI # 309

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

UNHRC proceedings on Xinjiang and the Oxfam report on reducing inequality

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2022 | IPRI # 308

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

North Korea's missile tests and Russia's annexation of four territories

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2022 | IPRI # 307

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Protests in Iran

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2022 | IPRI # 306

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Clashes between Armenia-Azerbaijan

read more

Conflict Weekly Cover Story

September 2022 | IPRI # 305

IPRI Comments

Bibhu Prasad Routray

Another Peace Accord in India’s Northeast: A review of the new agreement between New Delhi, Assam government and Adivasi insurgent groups

read more

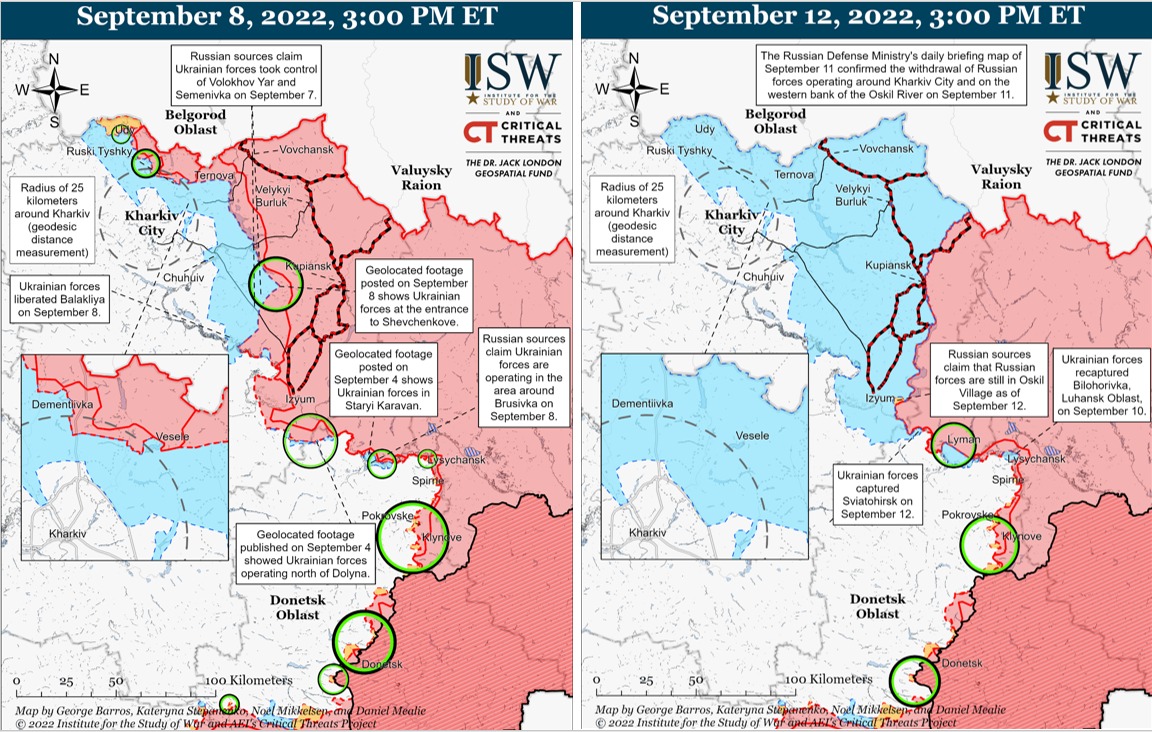

Conflict Weekly

September 2022 | IPRI # 304

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Ukraine's counter-offensive, North Korea's legislation on preemptive nuclear strike, and a report on Modern Slavery

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2022 | IPRI # 303

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The UN report on Xinjiang: Four Takeaways

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2022 | IPRI # 302

IPRI Comments

Violence in Baghdad and Renewed fighting in Ethiopia

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2022 | IPRI # 301

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Six months of War in Ukraine

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2022 | IPRI # 300

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Breaking from the past in Kenyan elections, a year under the Taliban in Afghanistan, and merciless heatwaves in Europe

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2022 | IPRI # 299

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Precarious ceasefire in Nagorno-Karabakh, fresh rounds of violence in Gaza, and the new US bill supporting climate change

read more

Conflict Weekly Cover Story

August 2022 | IPRI # 298

IPRI Briefs

Chrishari de Alwis Gunasekare

100 Days of People’s Protest in Sri Lanka: What’s Next?

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2022 | IPRI # 297

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Zawahiri's killing, Pope's apology to the indigenous people in Canada, Iraq's political crisis, and Senegal's disputed elections

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2022 | IPRI # 296

IPRI Briefs

Bibhu Prasad Routray

Myanmar Military: Annihilation as a Domination Strategy

read more

Conflict Weekly

July 2022 | IPRI # 295

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Ukraine grain deal, the Monkeypox emergency, and the US wildfires

read more

Conflict Weekly Cover Story

July 2022 | IPRI # 294

IPRI Comments

Amit Gupta

Killing Roe will hurt the US Soft Power

read more

Conflict Weekly

July 2022 | IPRI # 293

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Russia’s gas warning to Europe, and Sudan’s intra-tribal clashes

read more

Conflict Weekly

July 2022 | IPRI # 292

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

President Rajapaksa’s resignation and the economic crisis in Sri Lanka, and the military's withdrawal in Sudan

read more

Conflict Weekly

.jpg)

July 2022 | IPRI # 291

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Political Stalemate in Libya, and the Fall of Luhansk in Ukraine

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2022 | IPRI # 290

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Attacks on Europe's pride marches, the Morocco-Spain migration, and the intensifying Russia-Ukraine war

read more

NIAS Africa Studies

June 2022 | IPRI # 289

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

DRC-Rwanda tensions: Latest developments and issues

read more

NIAS Africa Weekly

June 2022 | IPRI # 288

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

Africa’s displacement crises: Three key drivers

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2022 | IPRI # 287

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Heatwave in Europe, rise of the Left in Colombia and the UNHCR report on Forced Displacement

read more

Russia-Ukraine War

June 2022 | IPRI # 286

IPRI Comments

Sruthi Sadhasivam

Limiting Ukraine War to Ukraine: The US foreign policy strategy

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2022 | IPRI # 285

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The new UK new bill on Brexit, Turkey's NATO concerns on Finland and Sweden and the SIPRI report on nuclear arsenal/weapons

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2022 | IPRI # 284

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

North Korea's Missile Tests and Sanctions on Mali

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2022 | IPRI # 283

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Denmark's referendum on EU defence and interstate tensions in Africa

read more

Conflict Weekly Cover Story

May 2022 | IPRI # 282

IPRI Briefs

Chrishari de Alwis Gunasekare

Sri Lanka’s Economic Crisis: Structural issues and impacts

read more

Conflict Weekly

May 2022 | IPRI # 281

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

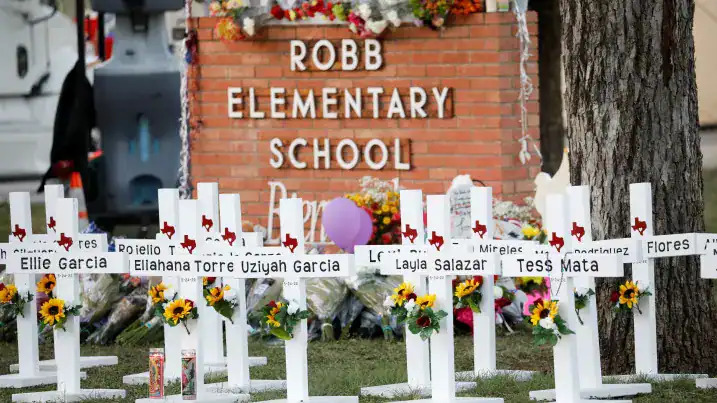

Another school shooting in the US, and EU-UK tussle over Northern Ireland protocol

read more

NIAS Africa Studies

May 2022 | IPRI # 280

IPRI Comments

Poulomi Mondal

Communal Tensions in Ethiopia: Five drivers

read more

Conflict Weekly

May 2022 | IPRI # 279

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Another racial attack in the US, Divide within the EU over the Russian oil ban, and violence in Israel

read more

Conflict Weekly Cover Story

May 2022 | IPRI # 278

IPRI Comments

S Shaji

Sudan, three years after Omar al Bashir

read more

Conflict Weekly

May 2022 | IPRI # 277

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Intensifying political crisis in Sri Lanka, Communal tensions in Ethiopia, and 75 days of Ukraine war

read more

NIAS Africa Studies

May 2022 | IPRI # 276

IPRI Comments

Mohamad Aseel Ummer

Wagner Group: Russia's Proxies or Ghost Soldiers?

read more

NIAS Africa Studies

May 2022 | IPRI # 275

IPRI Comments

Anu Maria Joseph

Mali ends defence ties with France: What does this mean

read more

Conflict Weekly

May 2022 | IPRI # 274

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Mali-France tensions and anti-UK protests in the Virgin Islands

read more

Conflict Weekly

April 2022 | IPRI # 273

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

​​​​​​​UK-Rwanda asylum deal, Mexico's continuing femicides, and Afghanistan's sectarian violenceÂ

read more

Conflict Weekly

April 2022 | IPRI # 272

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The battle for Donbas, Violence in Jerusalem, Riots in Sweden, Kyrgyzstan- Tajikistan border dialogue, and China’s military drills

read more

Conflict Weekly

April 2022 | IPRI # 271

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Violence in Nigeria, and Russia’s new military strategy in Ukraine

read more

Conflict Weekly

April 2022 | IPRI # 270

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Political Crises in Sri Lanka, Pakistan and Tunisia; Ceasefire in Yemen; and the Battle for Mariupol

read more

NIAS-IPRI Brief

April 2022 | IPRI # 269

IPRI Briefs

Sourina Bej

Ceasefire trails in Naga conflict: Space for peace parleys and violent politics

read more

NIAS-IPRI Brief

April 2022 | IPRI # 268

IPRI Briefs

Mohamad Aseel Ummer

Failing Peace in Darfur: Multiple Actors, No Outcome

read more

NIAS-IPRI Brief

April 2022 | IPRI # 267

IPRI Briefs

Jeshil Samuel J

The 2014 Gaza Ceasefire: A Stopgap to Peace dividend

read more

NIAS-IPRI Brief

April 2022 | IPRI # 266

IPRI Briefs

Dincy Adlakha

The 1999 Lome Peace Agreement: Issues and failed aspirations

read more

NIAS-IPRI Brief

April 2022 | IPRI # 265

IPRI Briefs

Anju C Joseph

Ceasefire in Moro Conflict: No lasting solution in sight

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2022 | IPRI # 264

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

30 days of War in Ukraine

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2022 | IPRI # 263

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Sri Lanka’s worsening economic crisis

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2022 | IPRI # 262

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The end of Denmark’s Inuit experiment

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2022 | IPRI # 261

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

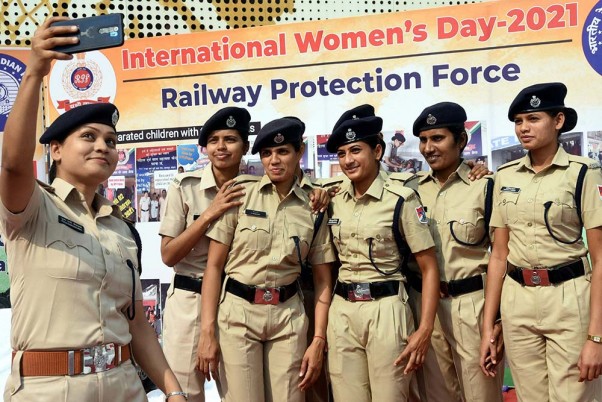

International Women’s Day: Gap between policies and realities on gender equality

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2022 | IPRI # 260

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Russia’s Ukraine Invasion: One Week Later

read more

Conflict Weekly

February 2022 | IPRI # 259

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Russia’s Ukraine salami slicing and Canada’s freedom convoy protests

read more

Conflict Weekly

February 2022 | IPRI # 258

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Unfreezing the Afghan assets, Tunisia’s judicial crisis and Libya’s new political deadlock

read more

Conflict Weekly

February 2022 | IPRI # 257

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Freedom convoy protests in Canada, and a de-escalation over Ukraine

read more

NIAS Africa Monitor

February 2022 | IPRI # 256

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

Coup in Burkina Faso: Five things to know

read more

Conflict Weekly

February 2022 | IPRI # 255

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

One year of the coup in Myanmar, Taliban meetings in Oslo, and the Global hunger report

read more

Conflict Weekly

January 2022 | IPRI # 254

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Coup in Burkina Faso, Continuing violence in Yemen, and an ISIS attack in Syria

read more

Conflict Weekly

January 2022 | IPRI # 253

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Threat of War over Ukraine, a Syrian trial in Germany, and Protests in France

read more

Central Asia

January 2022 | IPRI # 252

IPRI Comments

Abigail Miriam Fernandez

The unrest in Kazakhstan: Look beyond the trigger

read more

Conflict Weekly

January 2022 | IPRI # 251

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Unrest and crackdown in Kazakhstan, Another jail term for Aung San Suu Kyi, Two years after Qasem Soleimani, and Canada's reconciliation with the indigenous people

read more

Conflict Weekly

January 2022 | IPRI # 250

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

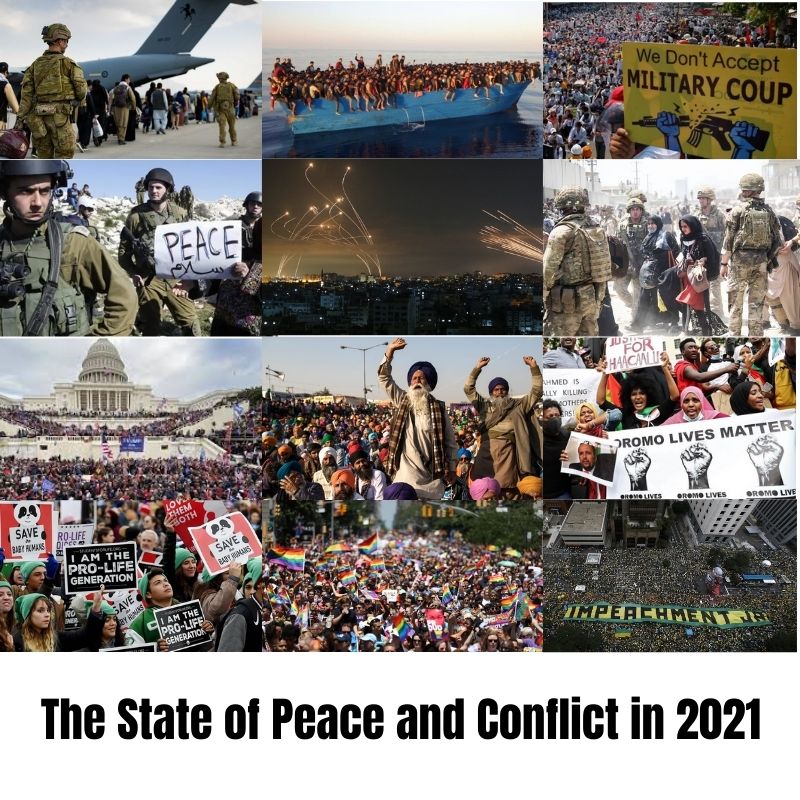

Conflicts in 2021 : Through Regional Prisms

read more

NIAS-IPRI Workshop

January 2022 | IPRI # 249

IPRI Briefs

Dr Shreya Upadhyay

State of Peace and Conflict in North America in 2021

read more

NIAS-IPRI Workshop

January 2022 | IPRI # 248

IPRI Briefs

Dr Aparaajita Pandey

State of Peace and Conflict in Latin America in 2021

read more

NIAS-IPRI Workshop

January 2022 | IPRI # 247

IPRI Briefs

Dr Shaji S

State of Peace and Conflict in Africa in 2021

read more

NIAS-IPRI Workshop

January 2022 | IPRI # 246

IPRI Briefs

Dr Stanly Johny

State of Peace and conflict in the Middle East in 2021

read more

NIAS-IPRI Workshop

January 2022 | IPRI # 245

IPRI Briefs

Dr Athar Zafar

State of Peace and Conflict in Central Asia in 2021

read more

NIAS-IPRI Workshop

January 2022 | IPRI # 244

IPRI Briefs

Dr Anshuman Behera

State of Peace and Conflict in South Asia in 2021

read more

NIAS-IPRI Workshop

.jpg)

January 2022 | IPRI # 243

IPRI Briefs

Dr Bibhu Prasad Routray

State of Peace and Conflict in Southeast Asia in 2021

read more

NIAS-IPRI Workshop

January 2022 | IPRI # 242

IPRI Briefs

Dr Sandip Kumar Mishra

State of Peace and Conflict in East Asia in 2021

read more

NIAS-IPRI Workshop

January 2022 | IPRI # 241

IPRI Briefs

Dr Anand V

State of Peace and Conflict in China in 2021

read more

Conflict Weekly

.jpg)

December 2021 | IPRI # 240

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Top 15 Conflicts in 2021

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2021 | IPRI # 239

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

New reports on the Omicron threat, and lifting sanctions on humanitarian aid to Afghanistan

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2021 | IPRI # 238

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

West warns Russia over Ukrainian aggression and South Korea and North Korean agree on end-of-war declaration in principle

read more

NIAS Africa Monitor

.jpeg)

December 2021 | IPRI # 237

IPRI Comments

Harshita Rathore

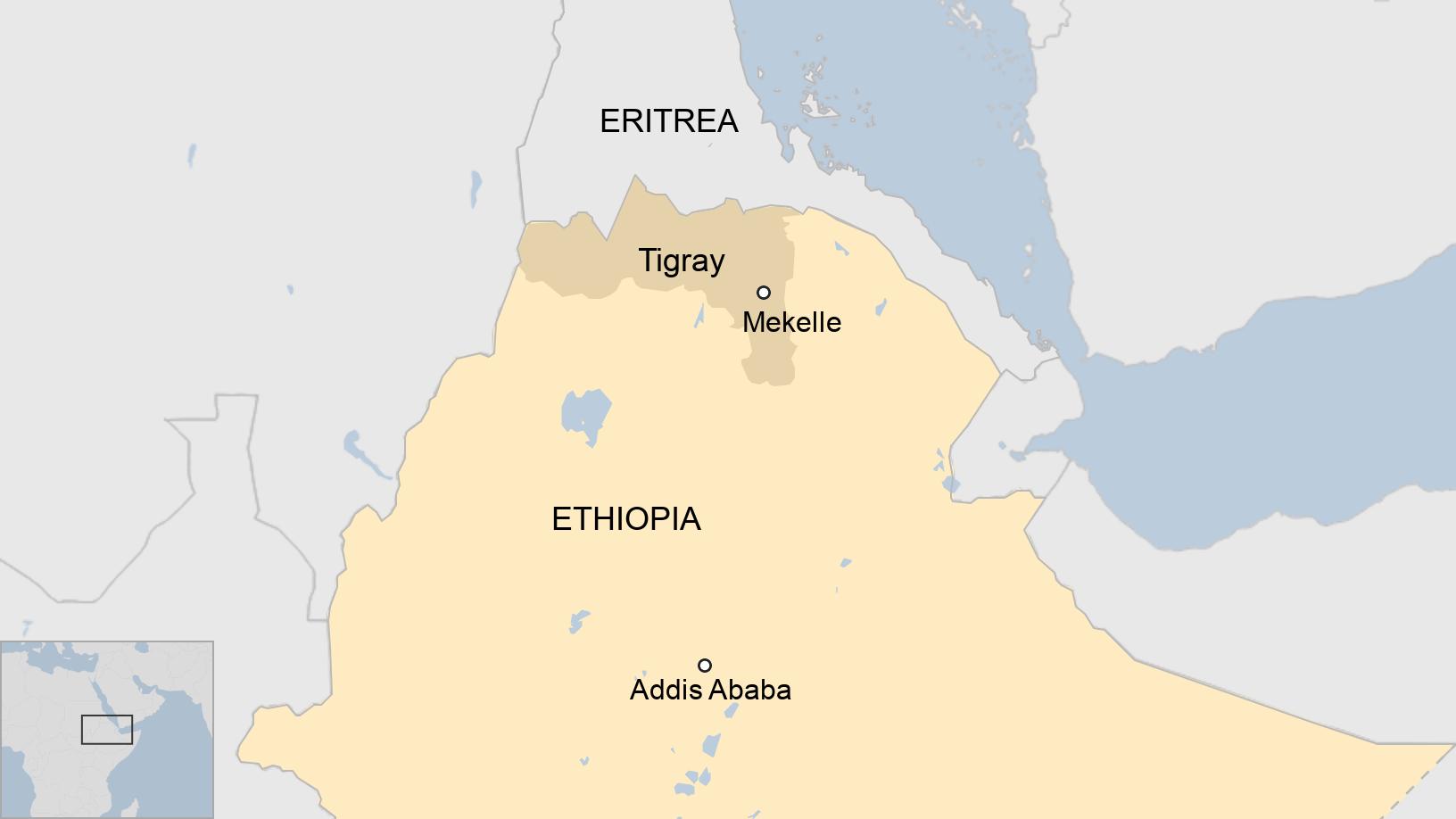

Famine in Ethiopia: The government's refusal to acknowledge, worsens the crisis

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2021 | IPRI # 236

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Conflict Weekly: 100th Issue

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2021 | IPRI # 235

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Unrest in the Solomon Islands, and the 12 million missing children in China

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2021 | IPRI # 234

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Anti-lockdown protests in Europe, Farmers' protests in India, and Continuing instability in Sudan

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2021 | IPRI # 223

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

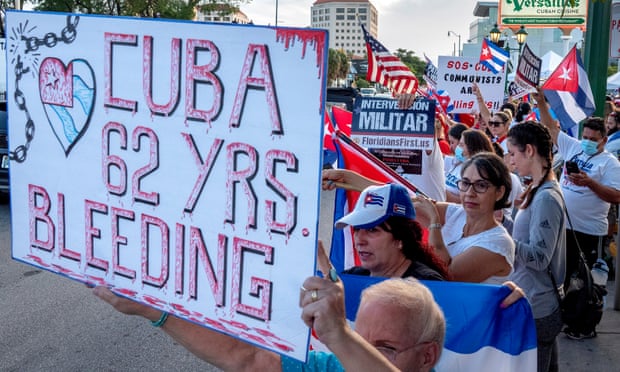

Europe's other migrant crisis, and Protests in Cuba and Thailand

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2021 | IPRI # 222

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The migrant threat to Europe from Belarus and Ceasefire with the TTP in Pakistan

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2021 | IPRI # 221

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

One year of Ethiopian conflict and UK-France fishing row

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2021 | IPRI # 220

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Coup in Sudan, Pressure on Myanmar's military regime, and the Migrant game by Belarus

read more

October 2021 | IPRI # 219

IPRI Comments

Vandana Mishra

The Texas abortion law: Five reasons why it is draconian

read more

Pakistan Reader Comments

October 2021 | IPRI # 218

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

No honour in honour killing

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2021 | IPRI # 217

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

One year after Samuel Paty's killing, Kidnapping in Haiti, and Instability in Sudan

read more

Conflict Weekly

.jpg)

October 2021 | IPRI # 216

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

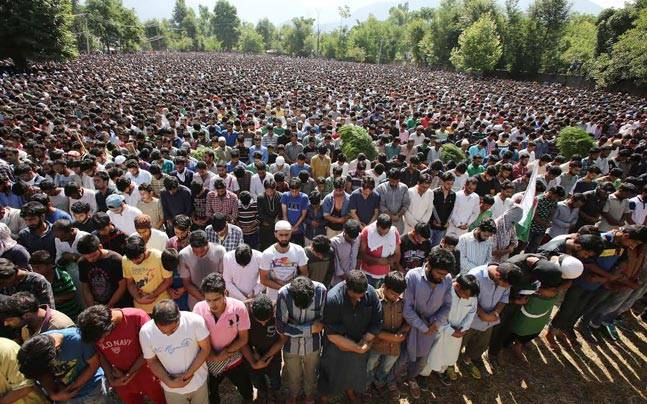

ISIS violence in Afghanistan, and Targeted killings in J&K

read more

Pakistan Reader Comments

October 2021 | IPRI # 215

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

Rising child abuse in Pakistan: Five reasons why

read more

Pakistan Reader Comments

October 2021 | IPRI # 214

IPRI Comments

Abigail Miriam Fernandez

Hazara Persecution in Pakistan: No end in sight

read more

Pakistan Reader Comments

October 2021 | IPRI # 213

IPRI Comments

D. Suba Chandran

Talking to the Pakistani Taliban: What did Imran say? And what does it mean? Is the rest of Pakistan ready for the same?

read more

Pakistan Reader Comments

October 2021 | IPRI # 212

IPRI Comments

D. Suba Chandran

Protests in Gwadar: Who and Why

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2021 | IPRI # 211

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Anti-Bolsonaro protests in Brazil, UK-France fishing row, Talks with the TTP in Pakistan, and the anti-abortion law protests in the US

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2021 | IPRI # 210

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Chinese White Paper on Xinjiang, and the Haitian migrant crisis in the US

read more

NIAS-IPRI Brief

September 2021 | IPRI # 209

IPRI Briefs

Apoorva Sudhakar

Africa’s Stolen Future:Child abductions, lost innocence, and a glaring reflection of State failure in Nigeria

read more

Afghanistan

September 2021 | IPRI # 208

IPRI Comments

Vineeth Daniel Vinoy

Who is who in the interim Taliban government? And, what would be the government structure?

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2021 | IPRI # 207

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Pride marches in Europe, Jail term for Hotel Rwanda hero, and continuing Houthi-led violence in Yemen

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2021 | IPRI # 206

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Protests in Europe and Brazil, and an impending humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan

read more

Latin America

September 2021 | IPRI # 205

IPRI Comments

Lokendra Sharma

Two months of Cuban protests: Is the ‘revolution’ ending?

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2021 | IPRI # 204

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

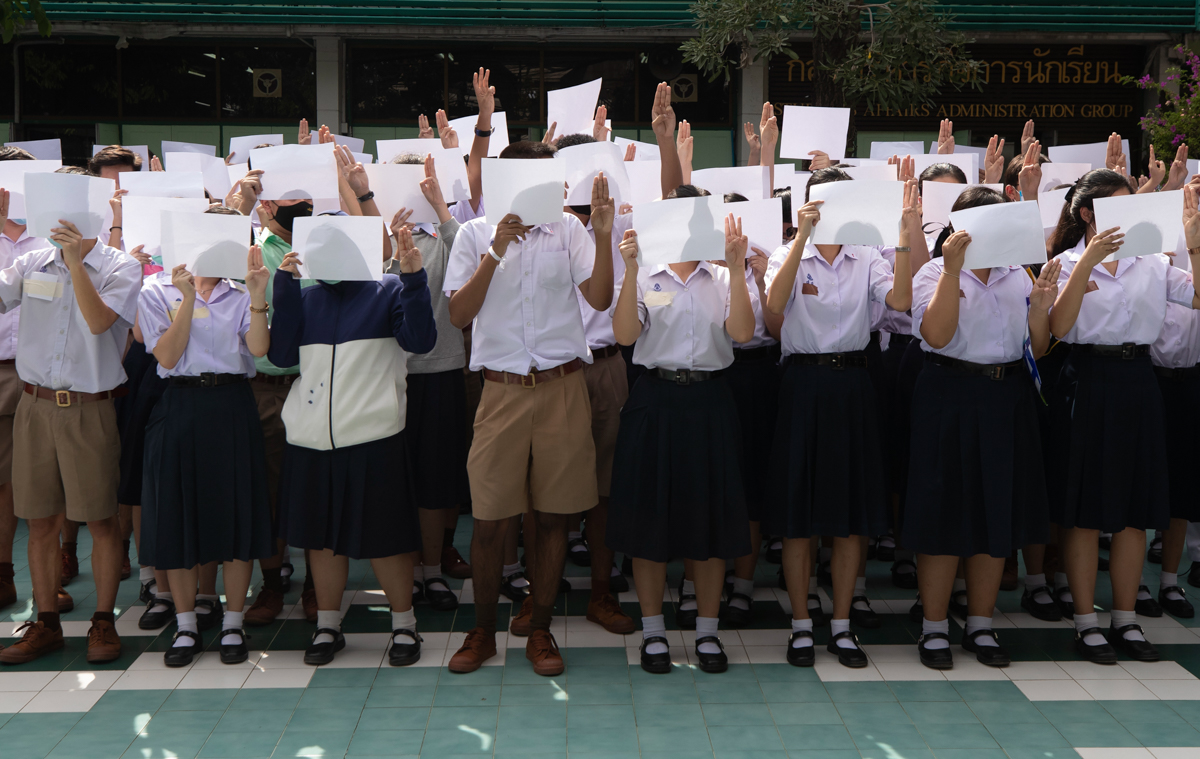

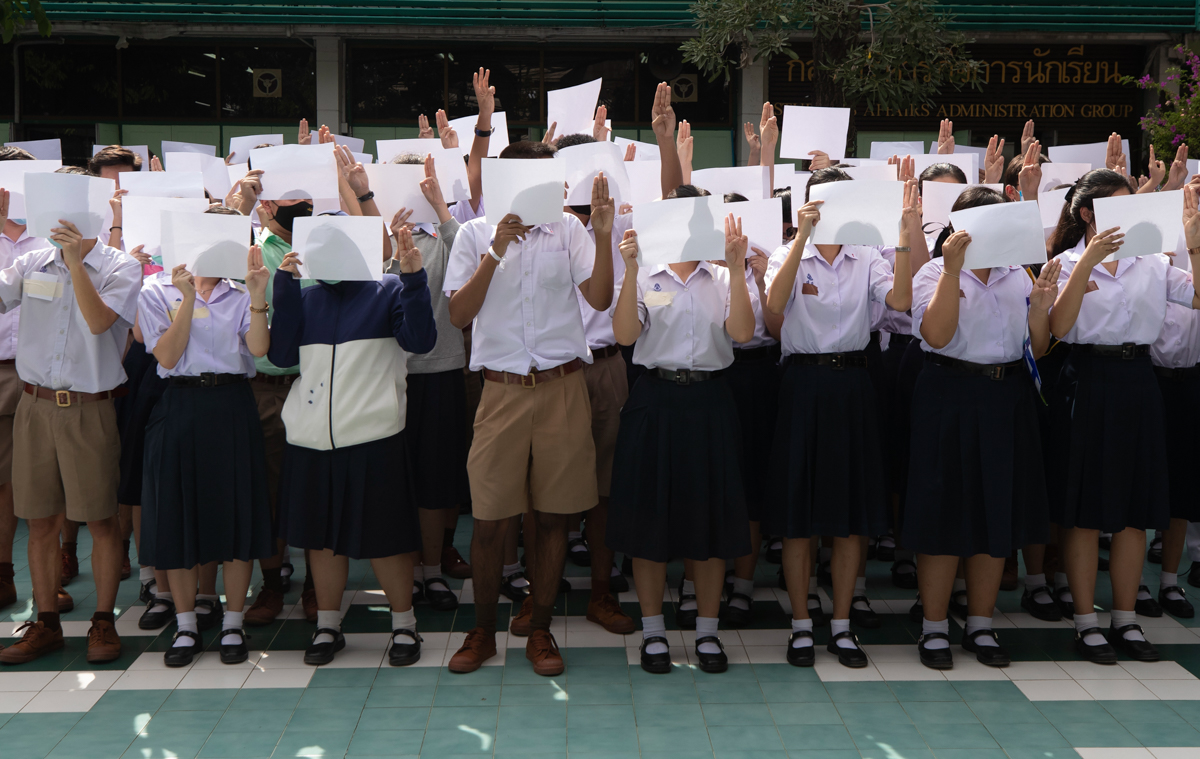

Texas' abortion ban, Return of the Thai protests, the Taliban government, and the Guinea coup

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2021 | IPRI # 203

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The US exit from Afghanistan, the Houthi violence in Yemen, and Hurricane Ida in the US

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2021 | IPRI # 202

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Chaotic evacuation in Kabul, Crimea Summit on seven years of Russian occupation, anti-lockdown protests in Australia, and continuing kidnappings in Africa

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2021 | IPRI # 201

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Return of the Taliban and the fall of Afghanistan

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2021 | IPRI # 200

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Protests return to Thailand, Taliban gains in Afghanistan, Pandemic action triggers protests in Europe, and new Climate Change report warns Code-Red

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2021 | IPRI # 199

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Taliban offensive, New Zealand's apology over the Pacific communities, Peru's new problem, and an inter-State clash in India's Northeast

read more

Conflict Weekly

July 2021 | IPRI # 198

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

France's anti-extremism bill, Canada's burning churches, and Tunisia's new political crisis

read more

NIAS Africa Monitor

July 2021 | IPRI # 197

IPRI Comments

Abigail Miriam Fernandez

Impending famine in Tigray, should make Ethiopia everyone's problem

read more

NIAS Africa Monitor

July 2021 | IPRI # 196

IPRI Comments

Anu Maria Joseph

Too late and too little is Ethiopia's international problem

read more

NIAS Africa Monitor

July 2021 | IPRI # 195

IPRI Comments

Sankalp Gurjar

Africa's Ethiopia Problem

read more

NIAS Africa Monitor

July 2021 | IPRI # 194

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

Ethiopia's Tigray problem is Tigray's Ethiopia problem

read more

Afghanistan

July 2021 | IPRI # 193

IPRI Comments

Abigail Miriam Fernandez

Five reasons why Afghanistan is closer to a civil war

read more

NIAS Africa Monitor

July 2021 | IPRI # 192

IPRI Comments

Anu Maria Joseph

Beyond the apology to Rwanda: In Africa, is France still a 'silent colonizer'?

read more

NIAS Africa Monitor

July 2021 | IPRI # 191

IPRI Comments

Mohamad Aseel Ummer

Migration in Africa: Origin, Drivers and Destinations

read more

NIAS Africa Monitor

July 2021 | IPRI # 190

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

15 of the 23 global hunger hotspots are in Africa:Three reasons why

read more

NIAS Africa Monitor

July 2021 | IPRI # 189

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

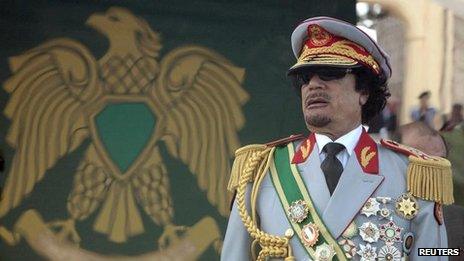

Libya: A new unity government and rekindled hope, a decade after the fall of Gaddafi

read more

Conflict Weekly

July 2021 | IPRI # 188

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Floods in Germany, Wildfires in Siberia and the Pegasus Spyware

read more

Conflict Weekly

July 2021 | IPRI # 184

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Anti-government protests in Cuba, Pro-Zuma protests in South Africa, and remembering the Srebrenica massacre

read more

Conflict Weekly

July 2021 | IPRI # 183

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Taliban offensive in Afghanistan, Protests in Colombia, and the Heat WaveÂ

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2021 | IPRI # 182

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Ceasefire in Ethiopia, Berlin Conference on Libya and the World Drug Report

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2021 | IPRI # 181

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The US Juneteenth, UN resolution on Myanmar and Global Peace Index

read more

Europe

June 2021 | IPRI # 180

IPRI Comments

Chetna Vinay Bhora

Spain, Morocco and the rise of rightwing politics in Europe over immigration

read more

Southeast Asia

June 2021 | IPRI # 179

IPRI Comments

Anju Joseph

Timor Leste: Instability continues, despite 19 years of independence

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2021 | IPRI # 178

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Three new reports on Child labour, Ethiopia and Xinjiang, Tensions in Belfast, and the Suu Kyi trial

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2021 | IPRI # 177

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The UN report on Taliban-al Qaeda links, Denmark on relocating refugee camps, Burkino Faso massacre, Arctic melt, and Afghan trilateral dialogue

read more

Israel-Palestine Conflict

June 2021 | IPRI # 176

IPRI Comments

Udbhav Krishna P

Revisiting the recent violence: Three takeaways

read more

Gender Peace and Conflict

June 2021 | IPRI # 175

IPRI Comments

Vibha Venugopal

The return of Taliban will be bad news for women

read more

Nepal

June 2021 | IPRI # 174

IPRI Comments

Sourina Bej

Fresh election-call mean unending cycle of instability

read more

Conflict Weekly

June 2021 | IPRI # 173

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Continuing protests in Colombia, another mass abduction in Nigeria, and a controversial election in Syria

read more

Conflict Weekly

May 2021 | IPRI # 172

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Ceasefire in Israel, NLD ban in Myanmar and a new Belarus crisis

read more

Conflict Weekly

May 2021 | IPRI # 171

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Elusive ceasefire in Israel-Palestine conflict, a migration crisis in Spain, three weeks of protests in Colombia, and the rise of Ransomware reign

read more

The Maldives

May 2021 | IPRI # 170

IPRI Comments

N Manoharan

The bomb attack on Mohamed Nasheed. Is it political or jihadist?

read more

Conflict Weekly

May 2021 | IPRI # 169

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Escalating Israel-Palestine violence, an attack and a ceasefire in Afghanistan, and the fallouts of Scotland election for the UK

read more

Australia's indigenous communities

May 2021 | IPRI # 168

IPRI Comments

Avishka Ashok

The systemic oppression continues despite three decades of the Royal Commission report

read more

Africa

May 2021 | IPRI # 167

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

15 of the 23 global hunger hotspots are in Africa. Three reasons why

read more

AfghanistanÂ

May 2021 | IPRI # 166

IPRI Comments

Abigail Miriam Fernandez

The US decision to withdraw is a call made too early. Three reasons why

read more

Conflict Weekly

May 2021 | IPRI # 165

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Violent protests in Colombia, US troops withdrawal in Afghanistan, and the battle for Marib in Yemen

read more

Conflict Weekly

April 2021 | IPRI # 164

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Israel-Syria missile strikes, Clashes in Somalia and Afghan meetings in Pakistan

read more

Conflict Weekly

April 2021 | IPRI # 163

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

George Floyd murder trial, Fukushima water release controversy, anti-France protests in Pakistan, Report on the Rwandan genocide and another Loya Jirga in Afghanistan

read more

Conflict Weekly

April 2021 | IPRI # 162

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Riots in Northern Ireland, Sabotage on an Iranian nuclear facility, and a massacre in Ethiopia

read more

Conflict Weekly

April 2021 | IPRI # 161

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Global gender gap report, Grand Ethiopian Renaissance Dam talks failure, Maoist attack in India, Border tensions between Russia and Ukraine, and the Security forces take control of Palma in Mozambique

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2021 | IPRI # 160

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Bloody Week in Myanmar, a Suicide attack in Indonesia and an Insurgency in Mozambique

read more

Conflict Weekly

March 2021 | IPRI # 159

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Sanctions on China, Saudi Arabia ceasefire in Yemen, the UNHRC resolution on Sri Lanka, and a massacre in Niger

read more

Conflict Weekly #62

March 2021 | IPRI # 158

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Gender Protests in Australia, Expanding Violence in Myanmar and Anti-protests bill in the UK

read more

Conflict Weekly # 61

March 2021 | IPRI # 157

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Women’s Day, Swiss Referendum, Myanmar Violence, George Floyd Trial and Lebanon Protests

read more

Conflict Weekly #60

March 2021 | IPRI # 156

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

From Myanmar and Hong Kong in Asia to Nigeria in Africa: Seven conflicts this week

read more

Conflict Weekly # 59

February 2021 | IPRI # 155

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Continuing Protests in Myanmar, ‘Comfort Women’ issue in South Korea and Abductions in Nigeria

read more

Ethiopia

February 2021 | IPRI # 154

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

Five fallouts of the military offensive in Tigray

read more

Afghanistan

February 2021 | IPRI # 153

IPRI Comments

Abigail Miriam Fernandez

The recent surge in targeted killing vs the troops withdrawal

read more

Abortions, Legislations and Gender Protests

February 2021 | IPRI # 152

IPRI Comments

Avishka Ashok

In Argentina, an extraordinarily progressive law on abortion brings the Conservatives to protest

read more

Abortions, Legislations and Gender Protests

February 2021 | IPRI # 151

IPRI Comments

Harini Madhusudan

In Poland, the protests against the abortion law feed into anti-government sentiments

read more

Abortions, Legislations and Gender Protests

February 2021 | IPRI # 150

IPRI Comments

Abigail Miriam Fernandez

In Honduras, a move towards a permanent ban on abortion laws

read more

Abortions, Legislations and Gender Protests

February 2021 | IPRI # 149

IPRI Comments

Sukanya Bali

In Thailand, the new abortion law poses more questions

read more

Myanmar

February 2021 | IPRI # 148

IPRI Comments

Aparupa Bhattacherjee

Civilian protests vs military: Three factors will decide the outcome in Myanmar

read more

Conflict Weekly # 58

February 2021 | IPRI # 147

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Anti-Separatism bill in France, Protests in Nepal against a gender-specific law, Surge in targetted killings in Afghanistan, and Instability continues in Ethiopia

read more

Conflict Weekly #57

February 2021 | IPRI # 146

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Anti-Coup protests in Myanmar, a new US strategy on Yemen, and the US-Iran differences on nuclear roadmap

read more

India and Sri Lanka

February 2021 | IPRI # 145

IPRI Comments

N Manoharan and Drorima Chatterjee

Five ways India can detangle the fishermen issue with Sri Lanka

read more

Conflict Weekly #56

February 2021 | IPRI # 144

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Coup in Myanmar and Protests in Russia

read more

Conflict Weekly #55

January 2021 | IPRI # 143

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Farmers' protests in India, Vaccine Wars, another India-China border standoff, and Navalny's imprisonment

read more

Conflict Weekly # 54

January 2021 | IPRI # 142

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

New President in the US, new Chinese Village in Arunachal Pradesh, new Israeli settlement in West Bank, and another massacre in Sudan

read more

Conflict Weekly # 53

January 2021 | IPRI # 141

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Trump impeached by the US House, Hazara miners buried in Pakistan, Farm laws stayed in India, and the Crisis escalation in CAR

read more

Conflict Weekly # 52

January 2021 | IPRI # 140

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

GCC lifts Qatar blockade, Iran decides to enrich uranium, Argentina legalizes abortion, French soldiers targeted in Mali, and the AFSPA extended in India's Northeast

read more

Conflicts around the World in 2020

December 2020 | IPRI # 139

IPRI Comments

Lakshmi V Menon

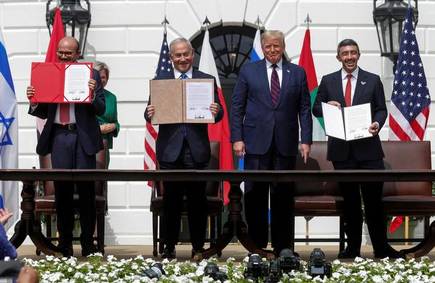

The Middle East: The Abraham Accords may be the deal of the century, but comes with a heavy Palestinian cause Â

read more

Conflicts around the World in 2020

December 2020 | IPRI # 138

IPRI Comments

Sourina Bej

France:  Needs to rethink  the state-religion relation in battling extremism

read more

Conflicts around the World in 2020

December 2020 | IPRI # 137

IPRI Comments

Teshu Singh

India and China: A tense border with compromise unlikely

read more

Conflicts around the World in 2020

December 2020 | IPRI # 136

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

Ethiopia: The conflict in Tigray and the regional fallouts

read more

Conflicts around the World in 2020

December 2020 | IPRI # 135

IPRI Comments

Kamna Tiwary

Europe: From anti-government protests in Belarus to ‘United for Abortion’ in PolandÂ

read more

Conflicts around the World in 2020

December 2020 | IPRI # 134

IPRI Comments

Harini Madhusudan

Brexit: A year of the UK-EU transition talks and finally, a DealÂ

read more

Conflicts around the World in 2020

December 2020 | IPRI # 133

IPRI Comments

Mallika Devi

Hong Kong: Slow Strangulation of Protests, Security Law and China's victory

read more

Conflicts around the World in 2020

December 2020 | IPRI # 132

IPRI Comments

Aparupa Bhattacherjee

Thailand: For the pro-democracy protests, it is a long march aheadÂ

read more

Conflicts around the World in 2020

December 2020 | IPRI # 131

IPRI Comments

Abigail Miriam Fernandez

Nagorno-Karabakh: Rekindled fighting, Causalities and a Ceasefire

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2020 | IPRI # 130

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Hot on the Conflict Trails: Top Ten Conflicts in 2020

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2020 | IPRI # 129

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Boko Haram abductions in Nigeria, Violence in Afghanistan and Farmers' protest in India

read more

Gender Peace and Conflict

December 2020 | IPRI # 128

IPRI Comments

Pushpika Sapna Bara

From Poland to India: More attacks on abortion rights coincide with the emergence of right

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2020 | IPRI # 127

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Farmers protest in India, Radicals target idols in Bangladesh, UK reaches out to the EU and Saudi Arabia to mend ties with Qatar

read more

Conflict Weekly

December 2020 | IPRI # 126

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

An assassination in Iran, Massacre in Nigeria and Suicide bombings in Afghanistan

read more

The Friday Backgrounder

November 2020 | IPRI # 125

IPRI Comments

D Suba Chandran

J&K: Ensure the DDC elections are inclusive, free and fair

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2020 | IPRI # 124

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Electoral violence in Africa, War crimes in Afghanistan, COVID's third global wave, and Protest escalation in Thailand

read more

Domestic turmoil and South Asia

November 2020 | IPRI # 123

IPRI Comments

Chrishari de Alwis Gunasekare

Sri Lanka’s 20-Amendment is more than what was bargained for

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2020 | IPRI # 122

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The US troops withdrawal, Violent protests in Thailand, Refugee crisis in Ethiopia, Anti-France protests in Pakistan and the Indo-Pak tensions along the LoC

read more

The Friday Backgrounder

November 2020 | IPRI # 121

IPRI Comments

D Suba Chandran

J&K: The Gupkar Alliance decides to fight the DDC elections together. The ballot may be thicker than principle

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2020 | IPRI # 120

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

A peace agreement in Nagorno-Karabakh and a brewing civil war in Ethiopia

read more

Conflict Weekly

November 2020 | IPRI # 119

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

IS terror in Vienna and Kabul, new controversy along Nepal-China border, and a boundary dispute in India’s Northeast

read more

J&K

October 2020 | IPRI # 118

IPRI Comments

D Suba Chandran

The Friday Backgrounder: Union Government amends the land laws, and the Kashmiri Opposition protests. There is politics in both

read more

GENDER AND PEACEBUILDING DURING A PANDEMIC

October 2020 | IPRI # 117

IPRI Comments

Kabi Adhikari

In Nepal, rising gender violence shadows COVID-19 pandemic

read more

GLOBAL PROTESTS MOVEMENT

October 2020 | IPRI # 116

IPRI Comments

Apoorva Sudhakar

Lebanon: One year of protests; it is more setbacks and little reforms

read more

GENDER AND PEACEBUILDING DURING A PANDEMIC

October 2020 | IPRI # 115

IPRI Comments

Chrishari de Alwis Gunasekare

In Sri Lanka, pandemic has eclipsed women’s role in peacebuilding

read more

J&K

October 2020 | IPRI # 114

IPRI Comments

Akriti Sharma

The new demands within the State over the Official Language Act

read more

India's Northeast

October 2020 | IPRI # 113

IPRI Comments

Sourina Bej

The Naga Peace talks: Caught in its own rhetoric, NSCN(IM) will lose its stakes

read more

J&K

October 2020 | IPRI # 112

IPRI Comments

Akriti Sharma

The Gupkar Declaration: Vociferous Valley and an Indifferent Jammu

read more

The Friday Backgrounder

October 2020 | IPRI # 111

IPRI Comments

D. Suba Chandran

J&K: Flag, Constitution, Media Freedom and Local Elections

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2020 | IPRI # 110

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Solidarity in France, Emergency withdrawn in Thailand, Terror tag removed in Sudan and Hunger in South Asia

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2020 | IPRI # 109

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Protests against sexual violence in Bangladesh, One year after Xi-Modi summit, Assassination of a Deobandi scholar in Pakistan and continuing violence in Yemen

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2020 | IPRI # 108

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

An Afghan woman nominated for the Nobel and a Dalit woman assaulted in India. External actors get involved in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict

read more

GENDER AND PEACEBUILDING DURING A PANDEMIC

October 2020 | IPRI # 107

IPRI Comments

Fatemah Ghafori

In Afghanistan, women peacebuilders need more than a seat at the table

read more

GENDER AND PEACEBUILDING DURING A PANDEMIC

October 2020 | IPRI # 105

IPRI Comments

Pushpika Sapna Bara

In India, pandemic relegates women peacebuilders to the margins

read more

Conflict Weekly

October 2020 | IPRI # 104

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Six million COVID cases in India, Abdullah Abdullah's visit to Pakistan, China's naval exercises in four seas, and the new tensions in Nagorno Karabakh

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2020 | IPRI # 103

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Al Qaeda module in India, Naga Peace talks and the Polio problem in Pakistan

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2020 | IPRI # 102

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Afghan summit in Doha, India-China Five Points agreement, Women protest in Pakistan, New amendment in Sri Lanka and the Bahrain-Israel rapprochement

read more

The Middle East

September 2020 | IPRI # 101

IPRI Comments

Samreen Wani

Lebanon: Can Macron's visit prevent the unravelling?

read more

Africa

September 2020 | IPRI # 100

IPRI Comments

Sankalp Gurjar

In Sudan, the government signs an agreement with the rebels. However, there are serious challenges

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2020 | IPRI # 99

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Targeted Violence in Pakistan, Protests in Hong Kong and the Charlie Hebdo Trial in France

read more

The Friday Backgrounder

September 2020 | IPRI # 98

IPRI Comments

D. Suba Chandran

J&K: The PDP meeting, Muharram clashes and the Kashmiri parties vis-Ã -vis Pakistan

read more

Conflict Weekly

September 2020 | IPRI # 97

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Anti Racist Protests in the US and the Floods in Pakistan

read more

Discussion Report

August 2020 | IPRI # 96

IPRI Comments

Sukanya Bali and Abigail Miriam Fernandez

Sri Lanka: Election Analysis, Expectations from the Government, Challenges Ahead, & a road map for India

read more

The Friday Backgrounder

August 2020 | IPRI # 95

IPRI Comments

D Suba Chandran

J&K: The Gupkar Resolution is a good beginning. So is the NIA charge sheet on the Pulwama Attack.

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2020 | IPRI # 94

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Proposed amendment in Sri Lanka, Verdict on the gunman in New Zealand, Peace Conference in Myanmar and the Ceasefire troubles in Libya

read more

The Friday Backgrounder

August 2020 | IPRI # 93

IPRI Comments

D. Suba Chandran

J&K: Baby steps taken. Now, time to introduce a few big-ticket items

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2020 | IPRI # 92

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Further trouble to the Naga Peace Talks, Taliban attack on woman negotiator, Protests in Thailand, Belarus and Bolivia, Israel-UAE Rapprochement, and the Oil Spill in Mauritius

read more

Friday Backgrounder

August 2020 | IPRI # 91

IPRI Comments

D Suba Chandran

J&K: Integration and Assimilation are not synonymous.

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2020 | IPRI # 90

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Release of Taliban prisoners in Afghanistan, Troubles in Naga Peace Talks in India’s Northeast, and a deadly week in Lebanon

read more

Friday Backgrounder

August 2020 | IPRI # 89

IPRI Comments

D Suba Chandran

J&K: One year later, is it time to change gears?

read more

Discussion Report

August 2020 | IPRI # 88

IPRI Comments

Chrishari de Alwis Gunasekare

Sri Lanka Elections 2020 - A Curtain Raiser: Issues, Actors, and Challenges

read more

Conflict Weekly

August 2020 | IPRI # 87

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

J&K a year after 5 August 2019, Militant ambush in Manipur, Environmental protests in Northeast India, and the return of street protests in Iraq

read more

Friday Backgrounder

July 2020 | IPRI # 86

IPRI Comments

D Suba Chandran

J&K: Omar Abdullah complains, there is no space for mainstream leaders. Should there be one?

read more

Conflict Weekly 28

July 2020 | IPRI # 85

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Floods in Bihar, Nepal and Bangladesh, Abduction of a journalist in Pakistan, Neutralization of militants in Srinagar and the UNAMA report on Afghanistan

read more

WOMEN, PEACE AND TWENTY YEARS OF UNSC 1325

July 2020 | IPRI # 84

IPRI Comments

Chrishari de Alwis Gunasekare

In Sri Lanka, 20 years later women still await the return of post war normalcy

read more

Friday Backgrounder

July 2020 | IPRI # 83

IPRI Comments

D. Suba Chandran

J&K: After the Hurriyat, is the PDP relevant in Kashmir politics today?

read more

Conflict Weekly 27

July 2020 | IPRI # 82

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Devastating floods in Assam, and a mob Lynching of cattle smugglers along India-Bangladesh border

read more

WOMEN, PEACE AND TWENTY YEARS OF UNSC 1325

July 2020 | IPRI # 81

IPRI Comments

Mehjabin Ferdous

In Bangladesh, laws need to catch up with reality

read more

Conflict Weekly 26

July 2020 | IPRI # 80

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Violence in India's Northeast, FGM ban in Sudan, the UN warning on Global Hunger & the Return of Global Protests

read more

Friday Backgrounder

July 2020 | IPRI # 79

IPRI Comments

D Suba Chandran

J&K: Four years after Burhan Wani

read more

Conflict Weekly 25

July 2020 | IPRI # 78

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Conflict and COVID in J&K, Dispute over constructing a temple in Islamabad, Return of the Indian fishermen into the Sri Lankan Waters, and the water conflict over River Nile in Africa

read more

Friday Backgrounder

July 2020 | IPRI # 77

IPRI Comments

D. Suba Chandran

The Rise, Fall and Irrelevance of Geelani. And the Hurriyat

read more

Conflict Weekly 24

July 2020 | IPRI # 76

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Geelani's Exit and Continuing Violence in J&K, and the BLA attack on Pakistan stock exchange in Karachi

read more

June 2020 | IPRI # 75

IPRI Comments

Sudip Kumar Kundu

Cyclone Amphan: West Bengal, Odisha limp back to a distorted normalcy

read more

June 2020 | IPRI # 74

IPRI Comments

Abigail Miriam Fernandez

An olive branch to the PTM in Pakistan: Will the PTI heed to the Pashtun rights movement

read more

Conflict Weekly 23

June 2020 | IPRI # 73

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Baloch Disappearance issue returns, Nepal tightens Citizenship rules, and Egypt enters the conflict in Libya

read more

Conflict Weekly 22

June 2020 | IPRI # 72

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Violence escalates along the India-China border, Cartographic tensions over India-Nepal border, Gas explosion in Assam and Deadly attacks by the Boko Haram in Nigeria

read more

Conflict Weekly 21

June 2020 | IPRI # 71

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Echoes of Black Lives Matter, Violence in Kashmir Valley, Rohingyas in the deep blue sea, One year of Hong Kong protests, Conflict in Libya and the human-wildlife conflict in South Asia

read more

Conflict Weekly 20

June 2020 | IPRI # 70

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

A week of violence in the US, Afghanistan and Africa, Urban drivers of political violence, and anti-racism protests in Europe

read more

Conflict Weekly 19

May 2020 | IPRI # 69

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Cyclone Amphan in the Bay of Bengal, Ceasefire in Afghanistan, Indo-Nepal border dispute in Kalapani, Honour Killing in Pakistan, New protests  in Hong Kong & the Anti-lockdown protests in Europe

read more

Conflict Weekly 18

May 2020 | IPRI # 68

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Kalapani dispute in India-Nepal border, Migrants exodus in India, Continuing violence in Balochistan and KP

read more

Conflict Weekly 17

May 2020 | IPRI # 67

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The return of Hong Kong Protests, a new Ceasefire in Myanmar, China-Australia Tensions on COVID & Trade, and the Al Qaeda-Islamic State clashes in Africa

read more

Conflict Weekly 16

May 2020 | IPRI # 66

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The Binge-fighting in Kashmir Valley, SIGAR report on Afghanistan, Killing of a PTM leader in Pakistan, the US Religious Freedom watchlist, and Haftar's ceasefire call in Libya

read more

Conflict Weekly 15

April 2020 | IPRI # 65

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

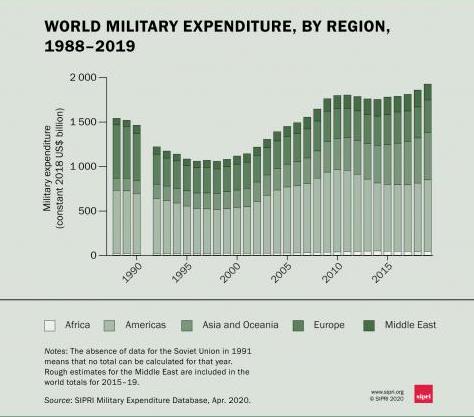

Ceasefire and Self Rule in Yemen, Syrian war trial in Germany, SIPRI annual report on military spending, and Low civilian casualties in AfghanistanÂ

read more

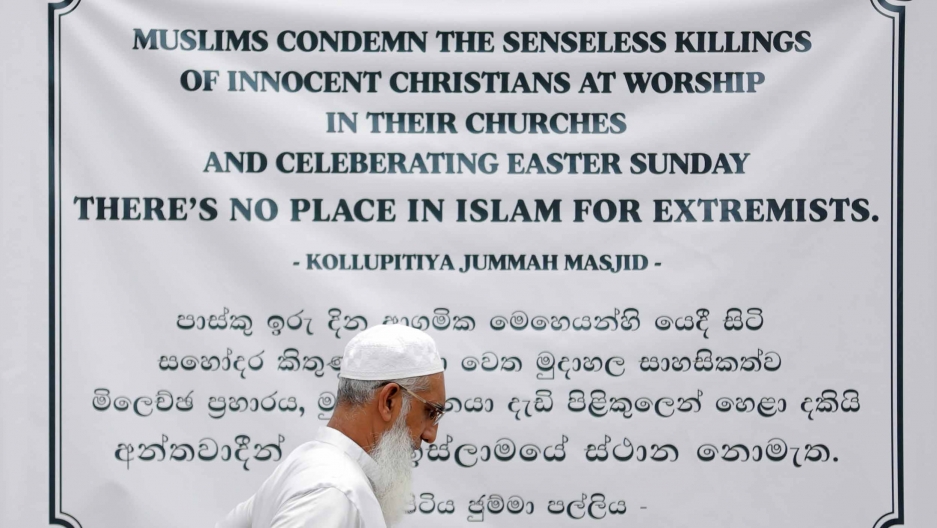

One year after the Easter Attacks in Sri Lanka

April 2020 | IPRI # 64

IPRI Comments

D Suba Chandran

Healing needs Forgiveness, Accountability, Responsibility and Justice

read more

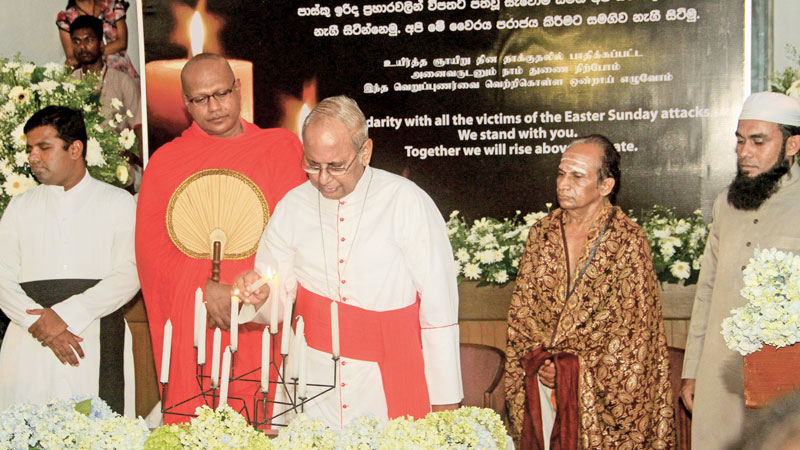

One year after the Easter Attacks in Sri Lanka

April 2020 | IPRI # 63

IPRI Comments

La Toya Waha

Have the Islamists Won?Â

read more

Conflict Weekly 14

April 2020 | IPRI # 62

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

A new wave of arrests in Hong Kong, One year after Easter Sunday attacks in Sri Lanka, ISIS violence in Mozambique, and the coming global Food Crisis

read more

COVID-19 and the Indian States

April 2020 | IPRI # 61

IPRI Comments

Alok Kumar Gupta

Jharkhand: Proactive Judiciary, Strong Civil Society Role, Rural Vigilantes

read more

COVID-19 and the Indian States

April 2020 | IPRI # 60

IPRI Comments

Alok Kumar Gupta

Bihar as Late Entrant: No Prompt Action, Punitive Measures, Migrant CrisisÂ

read more

COVID-19 and the Indian States

April 2020 | IPRI # 59

IPRI Comments

Anshuman Behera

Odisha’s Three Principles: Prepare for the Worst, Prepare Early, Prevent Loss of Lives

read more

COVID-19 and the Indian States

April 2020 | IPRI # 58

IPRI Comments

Niharika Sharma

New Delhi as Hotspot: Border Sealing, Curbing Fake News, Proactive leadership

read more

COVID-19 and the Indian States

April 2020 | IPRI # 57

IPRI Comments

Vaishali Handique

Northeast India: Civil Society in Unison, Media against Racism, Government’s Timely PreparednessÂ

read more

COVID-19 and the Indian States

April 2020 | IPRI # 56

IPRI Comments

Shyam Hari P

Kerala: Past Lessons and War-Footing response by the administration

read more

COVID-19 and the Indian States

April 2020 | IPRI # 55

IPRI Comments

Shilajit Sengupta

West Bengal: Proactive Local Leadership, Early Lockdown and Decentralised Action

read more

COVID-19 and the Indian States

April 2020 | IPRI # 54

IPRI Comments

P Harini Sha

Tamil Nadu’s Three Pronged Approach: Delay Virus Spread, Community Preparedness, Welfare SchemesÂ

read more

COVID-19 and the Indian States

April 2020 | IPRI # 53

IPRI Comments

Hrudaya C Kamasani

Andhra Pradesh: Early course correction, Independent leadership and Targeted Mitigation Â

read more

ONE YEAR AFTER THE EASTER ATTACKS IN SRI LANKA

April 2020 | IPRI # 52

IPRI Comments

Sanduni Atapattu

Preventing hatred and suspicion would be a bigger struggle

read more

ONE YEAR AFTER THE EASTER ATTACKS IN SRI LANKA

April 2020 | IPRI # 51

IPRI Comments

Chavindi Weerawansha

A majority in the minority community suffers, for the action of a few

read more

ONE YEAR AFTER THE EASTER ATTACKS IN SRI LANKA

April 2020 | IPRI # 50

IPRI Comments

Chrishari de Alwis Gunasekare

The Cardinal sermons for peace, with a message to forgive

read more

ONE YEAR AFTER THE EASTER ATTACKS IN SRI LANKA

April 2020 | IPRI # 49

IPRI Comments

Aparupa Bhattacherjee

Who and Why of the Perpetrators

read more

ONE YEAR AFTER THE EASTER ATTACKS IN SRI LANKA

April 2020 | IPRI # 48

IPRI Comments

Natasha Fernando

In retrospect, where did we go wrong?

read more

ONE YEAR AFTER THE EASTER ATTACKS IN SRI LANKA

April 2020 | IPRI # 47

IPRI Comments

Ruwanthi Jayasekara

Build the power of Co-existence, Trust, Gender and Awareness

read more

ONE YEAR AFTER THE EASTER ATTACKS IN SRI LANKA

April 2020 | IPRI # 46

IPRI Comments

N Manoharan

New ethnic faultlines at macro and micro levels

read more

ONE YEAR AFTER THE EASTER ATTACKS IN SRI LANKA

April 2020 | IPRI # 45

IPRI Comments

Asanga Abeyagoonasekera

A year has gone, but the pain has not vanished

read more

WOMEN, PEACE AND TWENTY YEARS OF UNSC 1325

April 2020 | IPRI # 44

IPRI Comments

Kabi Adhikari

In Nepal, it is a struggle for the women out of the patriarchal shadows

read more

WOMEN, PEACE AND TWENTY YEARS OF UNSC 1325

April 2020 | IPRI # 43

IPRI Comments

Jenice Jean Goveas

In India, the glass is half full for the women

read more

WOMEN, PEACE AND TWENTY YEARS OF UNSC 1325

April 2020 | IPRI # 42

IPRI Comments

Fatemah Ghafori

In Afghanistan, there is no going back for the women

read more

Conflict Weekly 13

April 2020 | IPRI # 41

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Executing Mujib's killer in Bangladesh, Continuing conflicts in Myanmar, Questioning Government's sincerity in Naga Peace Deal, Releasing Taliban prisoners in Afghanistan, and a report on damming the Mekong river by China

read more

Conflict Weekly 12

April 2020 | IPRI # 40

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Globally, Coronavirus increases Domestic Violence, deflates Global Protests, threatens Indigenous Communities and imperils the migrants. In South Asia, two reports question the Assam Foreign Tribunal and the Afghan Peace deal

read more

Afghanistan

April 2020 | IPRI # 39

IPRI Comments

Sukanya Bali

One month after the deal with the Taliban: Problems Four, Progress None

read more

Conflict Weekly 11

April 2020 | IPRI # 38

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Releasing a former soldier convicted of a war crime in Sri Lanka, Deepening of internal conflicts in Myanmar and the Taliban’s Deal is a smokescreen in Afghanistan

read more

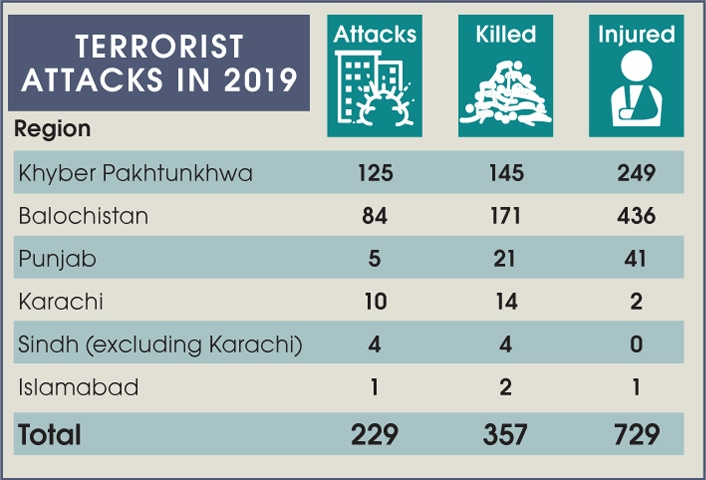

Report Review

March 2020 | IPRI # 37

IPRI Comments

Lakshmi V Menon

Pakistan: Decline in Terrorism

read more

Conflict Weekly 10

March 2020 | IPRI # 36

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

More violence in Afghanistan, Naxal ambush in India, Federal-Provincial differences in Pakistan's Corona fight, and a new report on the impact of CoronaVirus on Conflicts

read more

Conflict Weekly 09

March 2020 | IPRI # 35

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

The CoronaVirus: South Asia copes, China stabilises, Europe bleeds and the US wakes up finally

read more

Conflict Weekly 08

March 2020 | IPRI # 34

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Triumphant Women's march across Pakistan, Anti-CAA Protests in Dhaka, Â Two Presidents in Afghanistan, and Turkey-Russia Ceasefire in Syria

read more

Conflict Weekly 07

March 2020 | IPRI # 33

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Aurat March in Pakistan, US-Taliban Deal in Doha, Anti-CAA protest in Meghalaya, Sri Lanka’s withdrawal from the UNCHCR Resolution, and the problems of ceasefire in Syria and LibyaÂ

read more

Conflict Weekly 06

February 2020 | IPRI # 32

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Seven Days of Peace in Afghanistan, Violence in Delhi, Setback to Peace Talks on Libya and the Ceasefire in Gaza

read more

Conflict Weekly 05

February 2020 | IPRI # 31

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Afghan Election Results, US-Taliban Deal, Hafiz Saeed Conviction, Quetta Suicide Attack, Assam Accord, Mexico Femicide and the Climate Change impact on Bird Species

read more

Conflict Weekly 04

February 2020 | IPRI # 30

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Sri Lanka drops Tamil anthem, Assam looks for a new census for the indigenous Muslim population, Bangladesh faces a Rohingya boat tragedy and Israel witnesses resurgence of violence post-Trump deal

read more

Conflict Weekly 03

February 2020 | IPRI # 29

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Continuing Violence in Afghanistan, Bodo Peace Accord in Northeast India, Attack on the anti-CAA protesters in Delhi, and Trump's Middle East Peace Plan

read more

Conflict Weekly 02

January 2020 | IPRI # 28

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Bangladesh and ICJ's Rohingya Verdict, Taliban and Afghan Peace, Surrenders in India's Northeast, New government in Lebanon and the Berlin summit on Libya

read more

Conflict Weekly 01

January 2020 | IPRI # 27

IPRI Comments

IPRI Team

Nile River Agreement, Tehran Protests, Syrians meet in Berlin, Honduran Caravans in Mexico, Taliban's ceasefire offer, Quetta Suicide attack, Supreme court verdict on J&K and the Brus Agreement in Tripura

read more

Myanmar

October 2019 | IPRI # 26

IPRI Comments

Aparupa Bhattacherjee

Will prosecuting Suu Kyi resolve the Rohingya problem?

read more

Climate Change

October 2019 | IPRI # 25

IPRI Comments

Lakshman Chakravarthy N & Rashmi Ramesh

Four Actors, No Action

read more

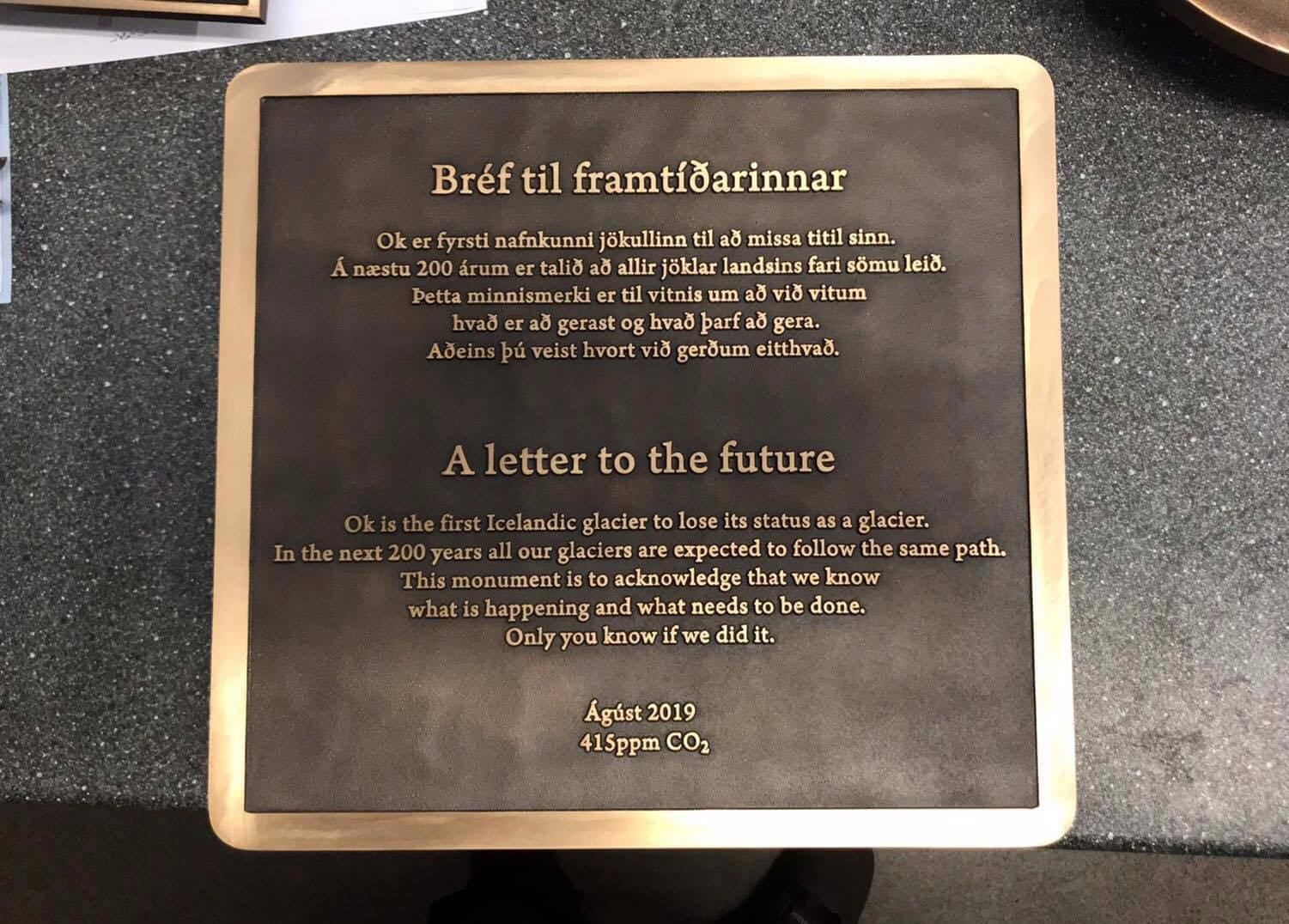

From Okjökull to OK:

September 2019 | IPRI # 24

IPRI Comments

Rashmi Ramesh

Death of a Glacier in Iceland

read more

The Hong Kong Protests:

August 2019 | IPRI # 23

IPRI Comments

Harini Madhusudan

Re-defining mass mobilization

read more

The Hong Kong Protest:

August 2019 | IPRI # 22

IPRI Comments

Parikshith Pradeep

Who Wants What?

read more

Africa

December 2020 | IPRI # 6

IPRI Briefs

Apoorva Sudhakar

Ballots and Bloodshed: Trends of electoral violence in Africa

read more

Myanmar

March 2019 | IPRI # 5

IPRI Comments

Aparupa Bhattacherjee

The Other Conflict in Rakhine State

read more

West Asia

February 2019 | IPRI # 4

IPRI Comments

Seetha Lakshmi Dinesh Iyer

Yemen: Will Sa'nna fall?

read more

China and Islam

February 2019 | IPRI # 3

IPRI Comments

Harini Madhusudhan

Sinicizing the Minorities

read more

Terrorism

January 2019 | IPRI # 2

IPRI Comments

Sourina Bej

Maghreb: What makes al Shahab Resilient?

read more

India's Northeast

July 2019 | IPRI # 1

IPRI Briefs

Titsala Sangtam

Counting Citizens: Manipur charts its own NRC

read more